The choir at Beauvais was rebuilt with much stronger buttresses, but an attempt in the sixteenth century to crown the building with a 153 meter tower, which would have made the cathedral the tallest structure in the world, resulted in further disaster when the tower fell down. Beauvais Cathedral remains admired as a great achievement of Gothic architecture, but it is also a reminder of the challenges confronted by medieval architects. These challenges and their solutions give us insights into what a craft approach might look like for the Internet of Things.

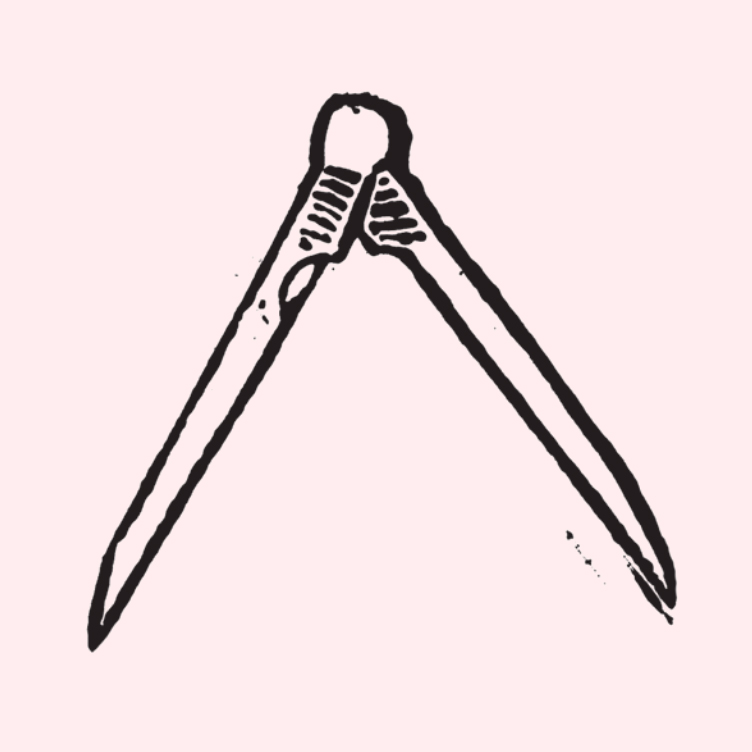

Medieval architects and masons had limited engineering and mathematical knowledge and used simple instruments. The enormous scale of medieval cathedrals was achieved by the repetition of simple geometric forms using such basic tools as a 45° square and dividers. The pattern of the ribs and shafts in vaults for example might have been calculated by simple rotation of a 45° square². The size of the buttresses were calculated by rules such as that given the fifteenth-century German master mason Lorenz Lechler:³

Medieval masons relied on repeating simple geometrical concepts, likewise, as Eric Raymond has pointed out: ⁴

The Credit Suisse global banking system dates back to the 1970s, and contains over 100 million lines of code written mainly in Java, C#, C++ and PL/1. Even a simple task like the introduction of the International Bank Account Number requires the rewriting of thousands of lines of code, with a risk that the vast edifice could come crashing down. Hundreds of projects updating the system are underway at any time, in just the same way as the medieval stonework of a cathedral is constantly undergoing a program of repair and replacement.⁵ The distinguished computer scientist and ‘software archaeologist’ Grady Booch has emphasised how software has evolved organically, declaring that:

How do these parallels between complex software systems and the procedures of medieval masons help us in thinking about the problems that confront us in today’s digital world? Some of the lessons are apparent in Eric Raymond’s remarkable book, The Cathedral and the Bazaar,⁴ Raymond draws a contrast between the carefully planned and managed environments of commercial software development, which Raymond compares to the medieval cathedral built with precision by a small group of experts, and the more ad hoc and organic approach associated with open source developments such as Linux, which Raymond suggests is like a crowded and bustling bazaar. Raymond’s book is an important one for Mozilla, since it helped inspire the act that created Mozilla, the release of the source for Netscape Communicator in 1998.

Some of Eric Raymond’s historical parallels don’t quite work. As we have seen, the approach to the creation of medieval cathedrals was much more organic and evolutionary than he suggests. On the other hand, markets in medieval Europe were much more strictly controlled than the idea of a bazaar suggests. But Eric Raymond’s fundamental point about how large structures can grow more effectively by communal and cooperative effort, working from the ground up, is one that is borne out by the medieval cathedral.

The moral of the building of the medieval cathedrals is about cultures of cooperation and shared effort. The most important point to emerge from contemplating the cathedrals concerns craft ways of thinking. Discussions about the role of craft in technology frequently focus on the way in which technology can be a material which the craftsman shapes and uses. But there are other aspects to craft thinking as well. One of these is the development of large structures organically through patterns of pragmatic development and repetition.

These craft characteristics are particularly evident with legacy code. Few projects are greenfield sites. You will probably inherit some code and other materials from earlier parts of the project. In the case of large systems, this code may be lenghty and may relate to a no longer supported operating system or computing technology. Michael Feathers calculates that in many development efforts the amount of legacy code may overwhelm the new code by factors of as much as 100:1 and even 1000:1. ⁷

Yet the legacy code still works. An immediate instinct may be to just rewrite it. Yet often this legacy code works perfectly well, and rewriting it runs the risk of breaking interdependencies elsewhere. The programmer is faced with exactly the same dilemma as the medieval mason. Do you change one bit of the building and risk another part of it falling down? For the medieval architect Lorenz Lechler, the test of any method was a pragmatic one: will it stand up and stay up? In programming, the “WTF” factor (how much swearing will a change to a program cause?) represents a similar pragmatic response.

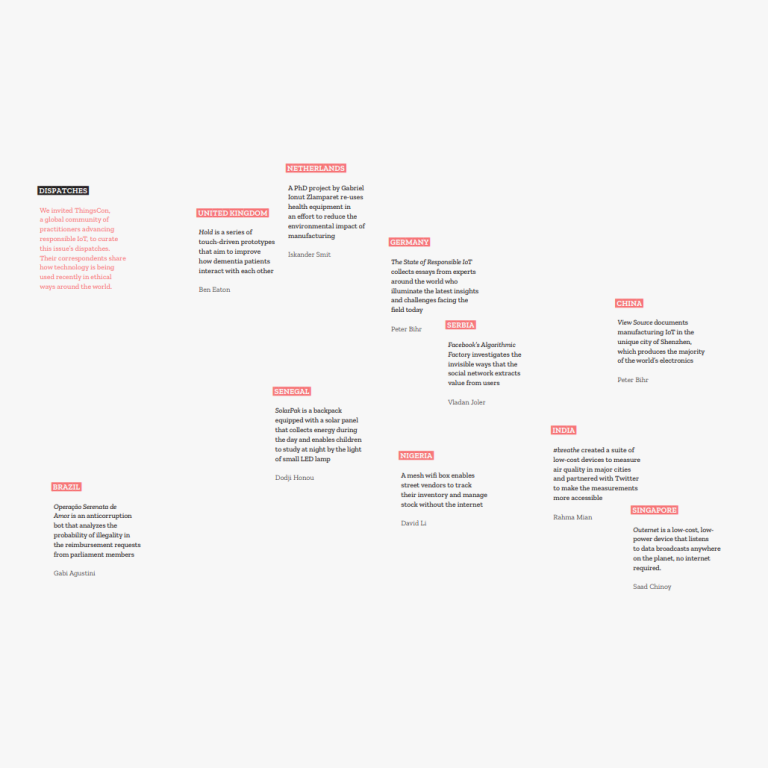

The simple techniques developed by medieval masons could be used to create huge edifices because masons had strong social networks to share their knowledge. The guilds and lodges of the medieval masons were like huge idea factories. Maybe, to assure the future health of the Internet of Things, we need a new form of guild.

2. Lon Shelby, ‘The Geometrical Knowledge of Medieval Master Masons’, Speculum 47, 1972, 395- 421, reprinted in Lynn Courtney, The Engineering of Medieval Cathedrals, Aldershot: Ashgate, 1997.

3. Lon Shelby and Robert Mark, ‘Late Gothic Structural Design in the “Instructions” of Lorenz Lechler’, Architectura 9:2, 1979, 113-31, reprinted in Courtney, Engineering of Medieval Cathedrals.