Quicksand’s projects have evolved through the years and a lot of them have taken us to interesting places where we have had the chance to delve into myriad contexts, and deeply embed ourselves – listening, observing and making – with humility and openness. I think it was a basic curiosity and our love for stories and travel that spurred our foray into human-centered design which is, at its core, about empathy and deep understanding of people’s needs and designing for those needs.

The Khadi movement¹ in India was framed as a non-violent protest against foreign control of the economic, cultural and artistic lives of the people. Gandhi insisted that the state empower villages to remain independent economic entities, with local production aligned with local consumption. It promoted a view of the Indian village (historically the truth of this view is disputed but mythically it still holds sway) that existed almost outside of history – as entities that were eternal and unchanging – that were generally left alone by political machinations that were concentrated in cities and frontier areas.

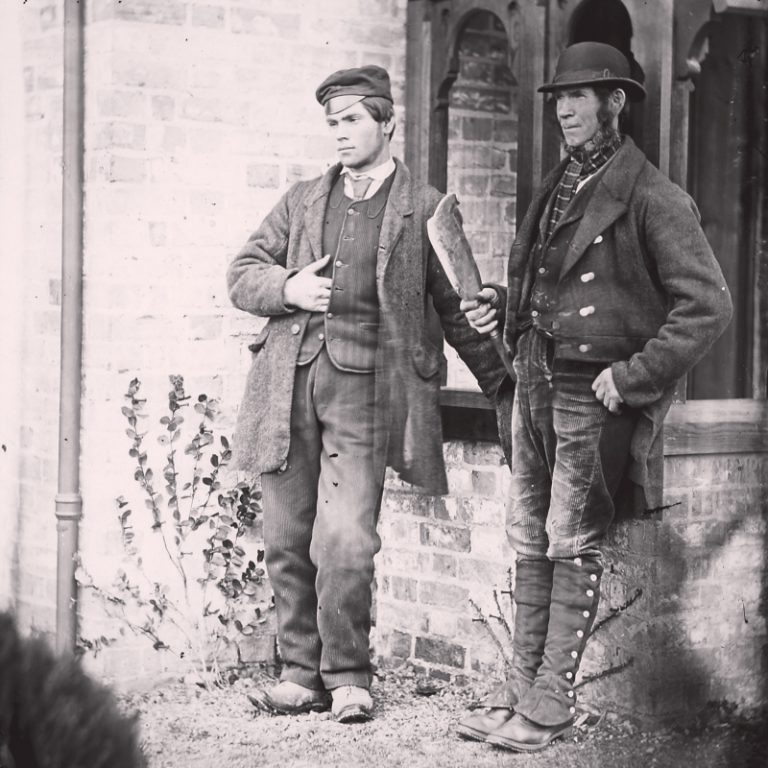

The Khadi process is done completely by hand, from spinning and weaving to dyeing. Santosh Koulagi (son of the founder of the trust, Surendra Koulagi), who handles the day to day operations of the trust told us that the original context in which the local craft of Khadi developed in this area has long disappeared.

The Khadi handloom industry was systematically compromised by state bodies tasked with its preservation. Rampant corruption and red-tapism from state bodies and the lack of social recognition combined to suffocate ambition and pride from the artisans. High skill and adeptness only seemed to be rewarded with poverty and extreme loss of pride. Thus, there are no more traditional weavers who are engaged with the craft, requiring training of a new group of individuals. Nevertheless, the trust has seen significant success in producing a modest line of garments for sale to urban audiences in neighboring Bangalore, Chennai and other cities. As with most discourses on revival, it is urban markets that are being counted upon as sources of revenue.

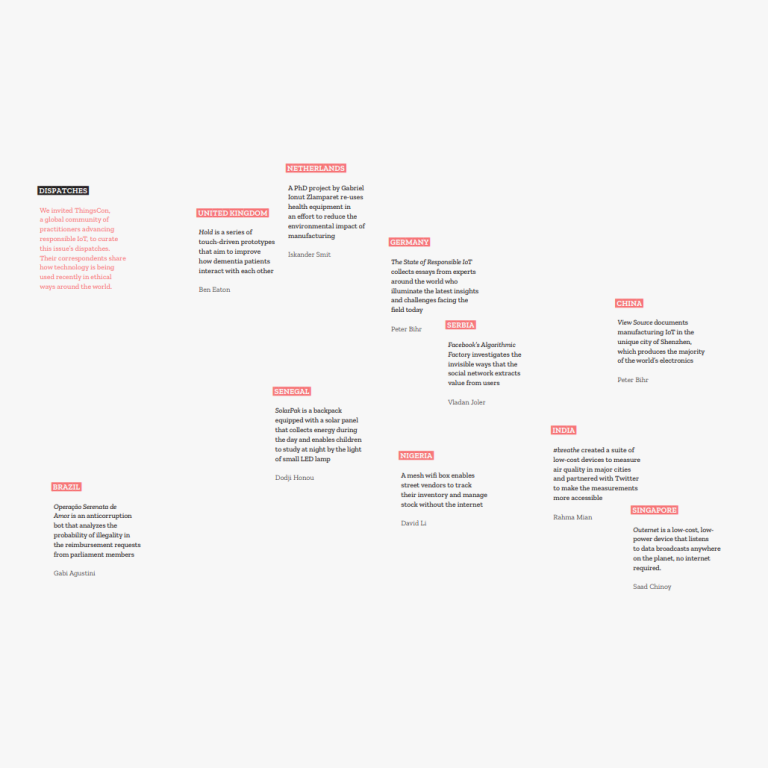

India has a rich tradition of decentralised practices that range from the political to the cultural. These practices, though under pressure now from centralizing market and political forces, are resilient and storehouses of rich traditional knowledge and expertise. Our effort was to learn from these communities, that on the surface are completely disconnected from the IoT discourse, but are in fact storehouses of thousands of years of knowledge and expertise around crafted methods that are embedded in their lives and communities as well as building decentralized means of production and livelihoods. A regular human-centered design brief would have attempted to uncover problems and co-create solutions for these. Instead, being able to approach these communities in a slow and considered manner, without the need to ‘design’ immediate solutions allowed us to learn about traditions and un-codified patterns that build trust without hierarchy, share information and expertise in decentralized systems, develop effective and sustainable production practices and build awareness around the impact of technologies on people.