We are presently thinking about the future. We seldom notice this, but most of our discussions of the past are future-oriented. We tend to our roots to assure our future growth. Practically, there’s no actual use for us to care even one bit about our past if it doesn’t inform our future. So it is quite clear why we obsessively document the past and why we invest so much in finding new ways to analyze it and to extract new insights towards the future. The unknown that lies ahead terrifies us; we want to eliminate this ambiguity. We want to predict the future. Now, we believe we might have finally found the right technology.

Data science and prediction algorithms are an exciting field in our long journey to uncover the future, but none of this is truly new. If the past teaches us anything, it is that every culture tried to expose the secrets that lie beyond the cliff of the present. Greek mythology protagonists consulted the Oracle of Delphi, the bearer of prophecy, to reveal what their destiny held. A recurring Greek tragedy trope pit these protagonists against their predetermined destiny. As they do anything in their power to disarm the prophecy, their action lead directly to its fulfillment. They did not willingly act towards fulfilling the prophecy; in fact, destiny is described as a predetermined narrative to which resistance is futile. Hence the self-fulfilling prophecy—a single, determinist, irreversible future—the past that is about to happen whether we like it or not.

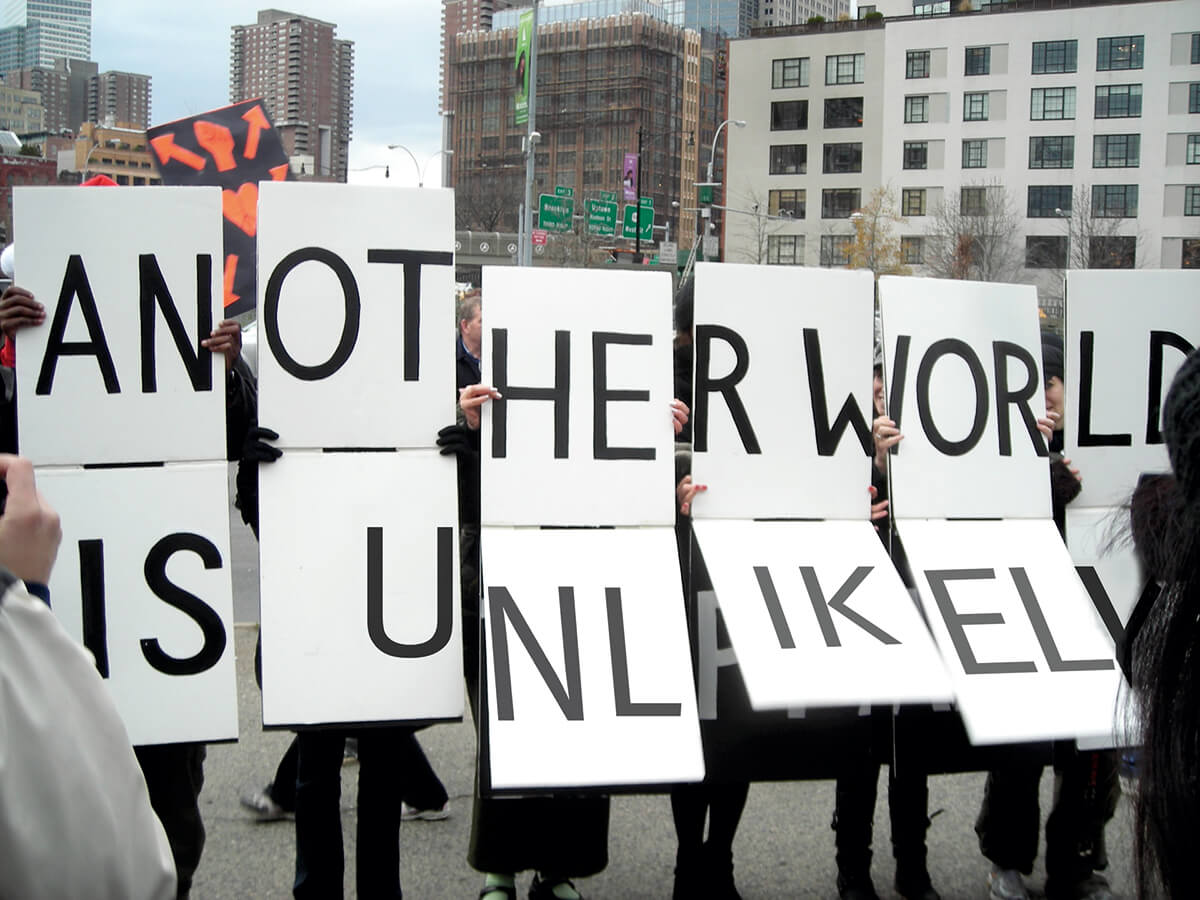

ANOTHER WORLD IS UNLIKELY

Prediction algorithms are our modern-day oracles; they extrapolate patterns and trends from the past into the future. In recent years we’ve seen this scientific approach to future-gazing spread as the true religion of the Liberal Left. Whether the Hilary Clinton campaign and its rational tone and policy, or the “Remain” campaign against Brexit. Both were rooting for passivity, for maintaining the status quo.

Examining the rhetoric on the opposing Conservative campaigns shows a much more active and empowering tone, committed to change and political agency: “Take Back Control” or “Make America Great Again”… It seems like the Right have embraced the progressive slogan that “Another World is Possible”. Or in other words: “Fuck the Status Quo!”

The data-driven predictions so eagerly embraced by the Liberal Left are inherently conservative. They are based on the premise that the patterns and trends of the past will continue into the future. They assume that history will simply repeat itself. According to these predictions, “Another World” is simply unlikely.

British and American voters have been trapped between two options: Status-Quo or Reactionism. But this is a false dichotomy between two inherently conservative philosophies. The first uses science and prediction algorithms to suppress change, and the second resists the status quo not through a vision for the future, but through an idealized vision of the past.

YOUR FUTURE IN A BLACK BOX

Futurists have become thought leaders in an intellectual world increasingly dominated by Silicon Valley’s brand of techno-cultural change. With book titles like “The Inevitable”, “What Technology Wants” or “The Singularity is Near”, tech-intellectuals like Kevin Kelly and Ray Kurzweil have been dishing business-friendly pseudo-scientific models for inevitable futures that we simply can’t resist. This brand of techno-determinism powered by economics might have monopolized not only the economy, but the right to imagine the future itself.

Forecasts inspired by algorithmic prediction define the future as a struggle between efficiency and agency. They are built on the premise that political change is statistically unlikely. The stable and therefore predictable status of the system becomes not only a prerequisite for algorithmic prediction but a condition to maintain. The more we’re dependent on prediction algorithms, the more we stand to lose from changing the status quo. Therefore most policy insights extracted from these models will attempt to suppress the uncertainty of political change and prefer repeating patterns from the past.

Algorithmic Neural Networks, today’s leading frameworks for artificial intelligence, are inspired by the little we know about how neural networks work in biological organisms. One of the biggest breakthroughs of this technology has been the realization that we don’t actually need to know how these artificial brains think to have them identify and even recreate precise patterns.

They eat data, find correlations, identify patterns and then spit knowledge. They allow us to outsource excess cognitive processes. As soon as they take over we can allow ourselves to forget how to do the job we just taught them. These frameworks perform best when run in an unsupervised mode. But this means they become mostly model-less black boxes, which limits our ability to scrutinize their actions and conclusions. We no longer remember phone numbers; that’s probably not such a big loss. We may soon no longer need to know how to drive; arguably a good thing too. My main concern with prediction algorithms is the de-skilling of our political imagination. We are forgetting how to imagine the future.

Data-driven algorithmic keys can only open doors they have previously encountered. Paradoxically, the mere fact we depend on these keys creates new conditions and hence we have no data to act upon. Information overload, filter bubbles, post-truth, faceless nihilistic trolling, online surveillance, the rise of multinational networked corporations and the challenge to state regulations, even the rapid refugee crisis and the looming climate catastrophe… if we don’t have existing data to crunch, how will we forecast our way out of this mess?

RESISTING THE FUTURE

It might be strange to argue we are suffering from a deficit of political imagination. Popular culture is obsessed with political speculative fiction. The Black Mirror TV series is a recurring reference for many debates about technology and The Handmaid’s Tale has become the political symbol of the #MeToo movement and the fight against the reactionary patriarchy.

There’s a race to the bottom to identify the marks of which literary dystopia we’re currently living in. Activists raise signs calling “Make Margaret Atwood Fiction Again!”. Others argue surveillance means we live in Orwell’s 1984. Or maybe today’s pop-technology is closest to Huxley’s Brave New World. Or the age of post-truth puts us in Philip K. Dick dystopia. While we can appreciate the critical sentiment, are we content with the reactionary notion of going backwards to our imagined past greatness?

Climate change is another data-driven dystopia. Though definitely non-fictional, its catastrophic terminology is similar: overwhelming, inevitable, too late… dystopias represent dark futures. They demand we appreciate what we have, as the future could take it away. The future is something to resist. “The worse the better.”

Lenin believed the old world needs to be destroyed for the new Communist utopia to rise from its ashes. Both dystopias and post-apocalyptic utopias are based on a failure of the imagination as they do not offer us a progressive model we can follow to deal with today’s existential threats. The climate crisis doesn’t present a clear target to resist, neither does it allow us the luxury of a clear cut from the old world. We have to come up with new ways forward, not only to detract us from looming doom, but to attract us towards new, maybe even desirable futures.

“There are many cruel and routine lies we tell to children but perhaps the most indicative is this: if you tell anyone your wish, it won’t come true.”

— Laurie Penny

CANCEL THE APOCALYPSE

In 1516 Thomas More wrote “Utopia”. In it, utopia was an island of abundance where private possession was abolished. This work stood as a unique and potent document of political imagination. Still today, we believe utopias depict what we stand to gain while dystopias describe what we may lose. So why is it so hard for us to say what we truly wish for? Studies in behavioral economics teach us that we are “risk-averse”; we hate losing roughly twice as much as we love to win. Dystopias are easier to imagine, like data-driven-determinism they are conservative—based on conserving what we have against the dangers of losing.

In the Center for Artistic Activism’s Imagining Utopia workshops, Stephen Duncombe and Steve Lambert adapt Utopian thinking for creative political activism. They ask activists to imagine “How would winning look?” When the activists discuss passing a law or blocking a policy, they add “…and then what?” As the activists hopes then become more ambitious, the facilitators ask again, “…and then what?” The task becomes harder and harder as the group’s utopia emerges, clarifying the core values, ethics and desires at the core of their politics.

In the 80s, Cyber Punk emerged as a leading science fiction genre depicting social anxieties from networking technologies, globalization and drug culture. Cyber Punk dystopias depicted lone protagonists rebelling against sinister control in the urban/digital decay. The retro-futurist Steam Punk genre followed, replacing cyberspace with the steam engine, but maintaining much of the Dystopian traits. In recent years we’ve seen a new science fiction genre emerge in the form of #SolarPunk. Started in Brazil, this genre takes inspiration from a different technological development – solar energy. The sun’s power and the distributed electric grid serve as both as an infrastructural backdrop and a political metaphor. In Solar Punk fiction, both electric and political power are distributed horizontally. And unlike Cyber Punks and Steam Punks, Solar Punks are unabashedly optimistic: the sky is blue, the fashion is festive and the city is drowned in greenery. In these visions technology and the environment are not at odds. These are futures worth fighting for.

FUTURES, PLURAL.

Utopias have grown out of fashion.In the 20th Century modernist political ideologies led us to rightfully suspect Utopian dreams. Fighting in the names of both the Communist and Nazi Utopias led to wars and genocide. More recently, the Islamic State’s fundamentalist utopia ravages the Middle East. Much like “One man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter”, one person’s dystopia is another utopia.

Both Utopias and Dystopias are essential for us to retrieve our political imagination. The two function together as attractors and detractors. We use Utopias as guiding lights, and Dystopias to make sure we haven’t lost our way.

So far we’ve only scratched the surface with neural networks that extrapolate the status quo. Neural Networks’ current working assumption is that correlation may not equal causation, but it’s close enough… To “cancel the apocalypse”, the model we suggest is reversed: define a cause and then work to discover and make possible the correlations that would advance it. Unlike the past which we can mine for data and analyze for insight, “the future” doesn’t exist. We always have “futures”, plural. We should consider the probable, the possible, the desirable. We should imagine attractors and detractors, utopias and dystopias. We should use data to inform decisions not dictate them. We should use automation to extend autonomy, not limit it. We should reclaim our political imagination.

“She’s on the horizon:

I go two steps,

she moves two steps away.

I walk ten steps,

and the horizon runs ten steps ahead.

No matter how much I walk,

I’ll never reach her.

What good is Utopia?

That’s what:

it’s good for walking.”— Eduardo Galeano / Walking Words (1995)