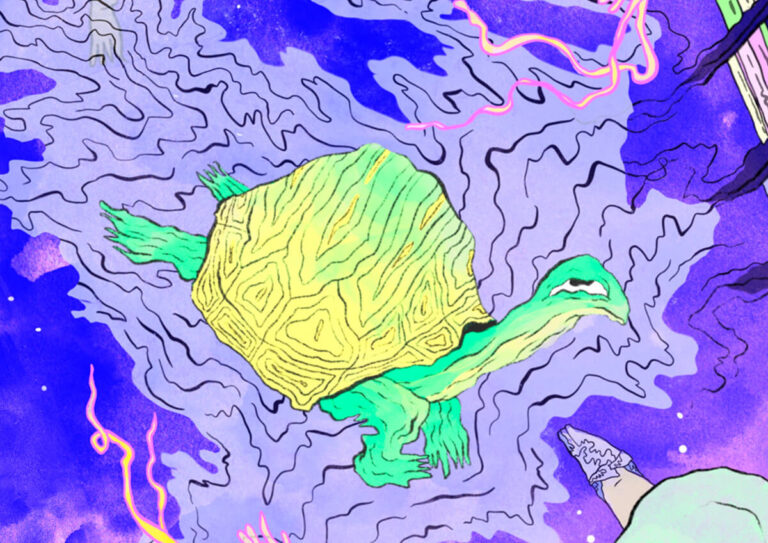

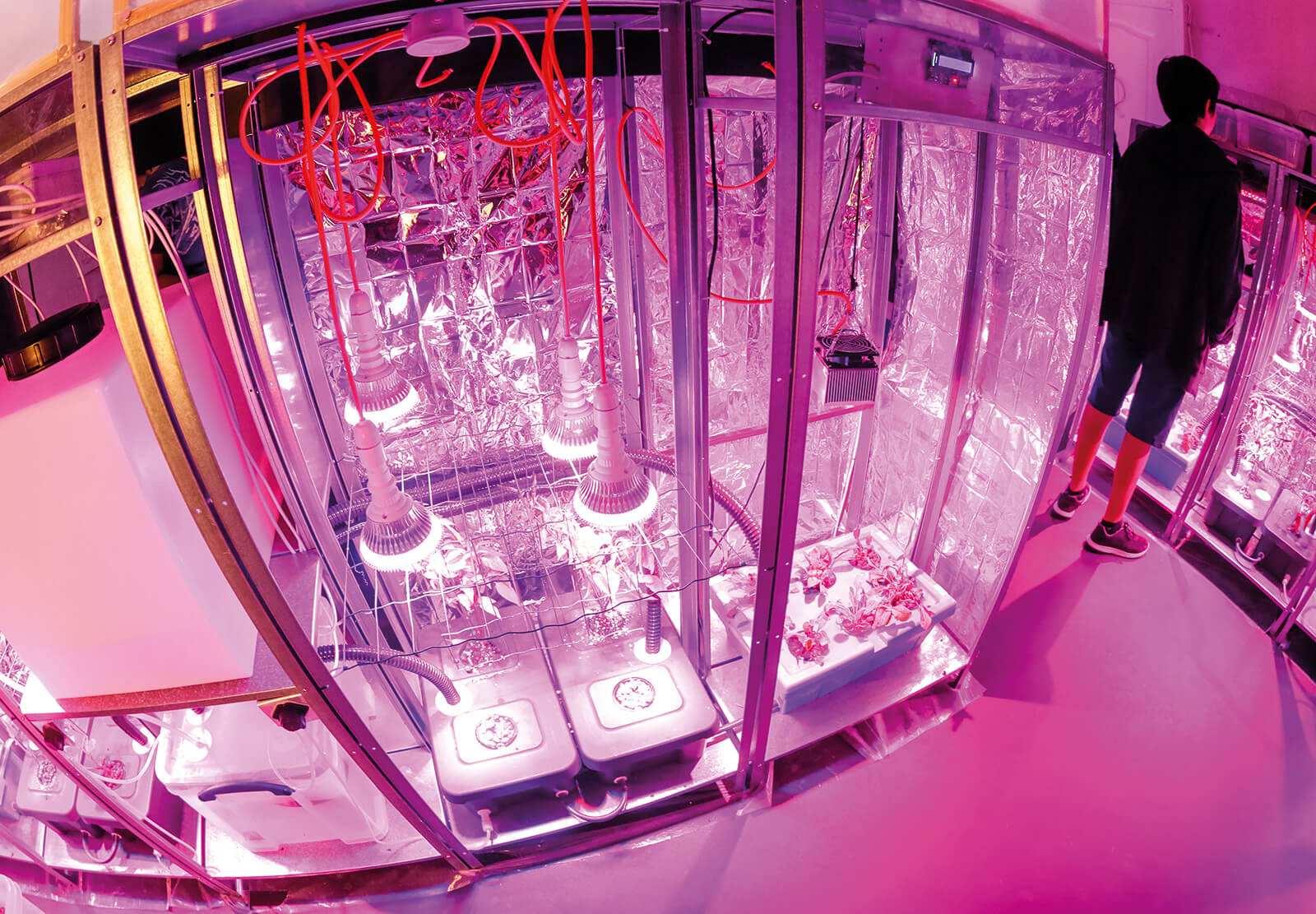

Images from the installation “Mitigation of Shock” by Superflux

Perhaps the best, or maybe worst, place to start is by exposing my greatest fear. I am scared of death. But not as scared as I used to be. From around the age of 10 to my early teens I collected, in the archive of my head, hundreds of my imagined deaths. Traveling in the train through the dark Indian desert, I would imagine being shot from somewhere far out in the distance.

Or rushing through chaotic Ahmedabad traffic I would imagine the railway bridge falling on me. Even though it would have been easy enough, I resisted the lure of religious spirituality—and instead found my spiritual home in cinema. It is from this that I look to the future. A future that, when my son is my age, will be incredibly worrying.

Based on the current global projections for both the massive increase in human population and the huge decrease in available land to feed them from, we worked on a project exploring a future where the Western world has moved from abundance to scarcity. We imagined living in a future city with repeated flooding, periods with almost no food in supermarkets, economic instabilities, broken supply chains. We asked ourselves, what can we do to not just survive, but prosper in such a world? What food can we eat? This inquiry became the basis of our installation ‘Mitigation of Shock’ commissioned by CCCB Barcelona and curated by José Luis de Vincente.

The installation transports you to a London flat, perhaps in the year 2050 or so—when my son might be around our age. At first glance, you’re in a seemingly comfortable living space designed for a world of automated living, global trade and material abundance. Then on closer inspection, you realise the apartment has been adapted to a future it was never meant to inhabit. Discarded newspapers and a radio show reflect the tensions of this new world; recipes in the kitchen reveal the change in food production, storage, and consumption. Experimental food production occupies space once given to relaxation—transforming the apartment into a space for growing and producing food. Towering silver stacks of mushrooms, cabbages and chili plants flourish in an optimally lit indoor environment.

The installation transports you to a London flat, perhaps in the year 2050 or so—when my son might be around our age. At first glance, you’re in a seemingly comfortable living space designed for a world of automated living, global trade and material abundance. Then on closer inspection, you realise the apartment has been adapted to a future it was never meant to inhabit. Discarded newspapers and a radio show reflect the tensions of this new world; recipes in the kitchen reveal the change in food production, storage, and consumption. Experimental food production occupies space once given to relaxation—transforming the apartment into a space for growing and producing food. Towering silver stacks of mushrooms, cabbages and chili plants flourish in an optimally lit indoor environment.As part of the installation, Jon built a food computer from scratch—something he hadn’t done before. We used the soilfree, nutrient-enriched water vapour technique of fogponics to grow things quickly. We wanted to build them in the cheapest way possible: from salvaged, abandoned and repurposed materials. Turning today’s waste into tomorrow’s dinner.

One of the things that I found incredibly fascinating was the growth of the humble mushroom—this mycelium we tried to grow in so many ways. We used Arduinos and ultrasonic fog to control the humidity in the DIY polythene-clad box that had become our fruiting chamber. For a while nothing much happened. Then suddenly it began to find its right environment, or rather our human activities and disturbances, both planned and unplanned, had created the optimum conditions for it to grow. Eventually it grew into this beautiful brightly coloured and quite delicious form. This direct experience drew us into the world of many interacting species. It provided a useful vantage point for knowing ourselves as participants in more complex human and non-human relationships.

This inspired me to think of a bigger picture, and instead of the established “user-centred design” narrative so loved by technology companies and design schools alike, I considered a “more-than-human” centred approach. Where humans beings are not at the centre of the universe and the centre of everything. Where we consider ourselves as deeply entangled in relationships with other species and non-human entities.

This inspired me to think of a bigger picture, and instead of the established “user-centred design” narrative so loved by technology companies and design schools alike, I considered a “more-than-human” centred approach. Where humans beings are not at the centre of the universe and the centre of everything. Where we consider ourselves as deeply entangled in relationships with other species and non-human entities.

Our profession, and those we serve after a long time, finally have come around to the idea of human-centred design, which is important for many reasons, especially when designing for diverse users and communities. But, in a broader context, as multi species anthropologist Anne Galloway writes: “what if we deny that human beings are exceptional? What if we stop speaking and listening only to ourselves?”

Galloway continues, “Complementary ways of thinking, doing, and making emphasise the practice of care and imagination and challenge us to work with, not against, vulnerability, humility and interdependence.” Interdependence is a powerful concept for me: different participants—human and non-human—are emotionally, economically, ecologically or morally interdependent on each other. And this reliance is acknowledged. I think this perspective is something that would be very meaningful for many of us to consider—whether we’re interaction, service, or UX designers, entrepreneurs, researchers or people who put things out in the world for others “to use”.

This inspired me to think of a bigger picture, and instead of the established “user-centred design” narrative so loved by technology companies and design schools alike, I considered a “more-than-human” centred approach. Where humans beings are not at the centre of the universe and the centre of everything. Where we consider ourselves as deeply entangled in relationships with other species and non-human entities.

This inspired me to think of a bigger picture, and instead of the established “user-centred design” narrative so loved by technology companies and design schools alike, I considered a “more-than-human” centred approach. Where humans beings are not at the centre of the universe and the centre of everything. Where we consider ourselves as deeply entangled in relationships with other species and non-human entities.Our profession, and those we serve after a long time, finally have come around to the idea of human-centred design, which is important for many reasons, especially when designing for diverse users and communities. But, in a broader context, as multi species anthropologist Anne Galloway writes: “what if we deny that human beings are exceptional? What if we stop speaking and listening only to ourselves?”

Galloway continues, “Complementary ways of thinking, doing, and making emphasise the practice of care and imagination and challenge us to work with, not against, vulnerability, humility and interdependence.” Interdependence is a powerful concept for me: different participants—human and non-human—are emotionally, economically, ecologically or morally interdependent on each other. And this reliance is acknowledged. I think this perspective is something that would be very meaningful for many of us to consider—whether we’re interaction, service, or UX designers, entrepreneurs, researchers or people who put things out in the world for others “to use”.

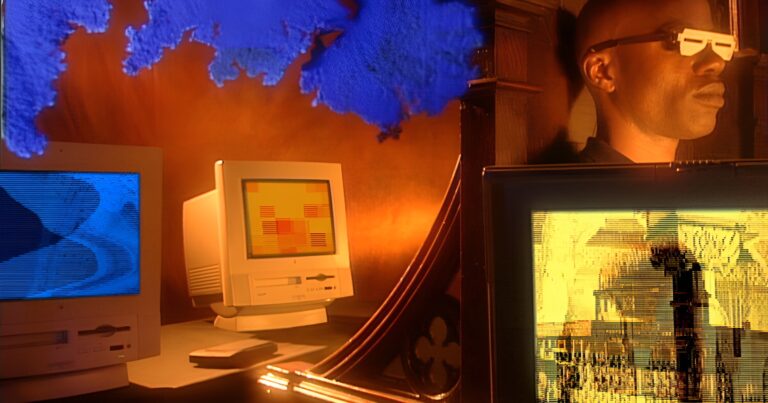

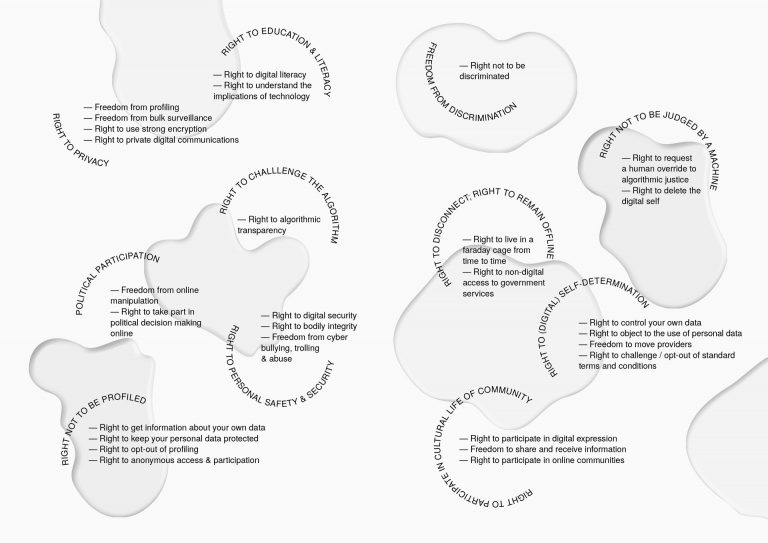

Apart from climate change, another reason to consider this form of interdependence is much closer to home. Today, we are already living amidst other kinds of non-human entities, increasingly autonomous things and systems that are very seductive. But beneath the gloss of technological utopia, it is becoming obvious how these computers, tools and machines that we have created in order to master the world are remastering us: our politics, the way we relate to each other and the world around us.

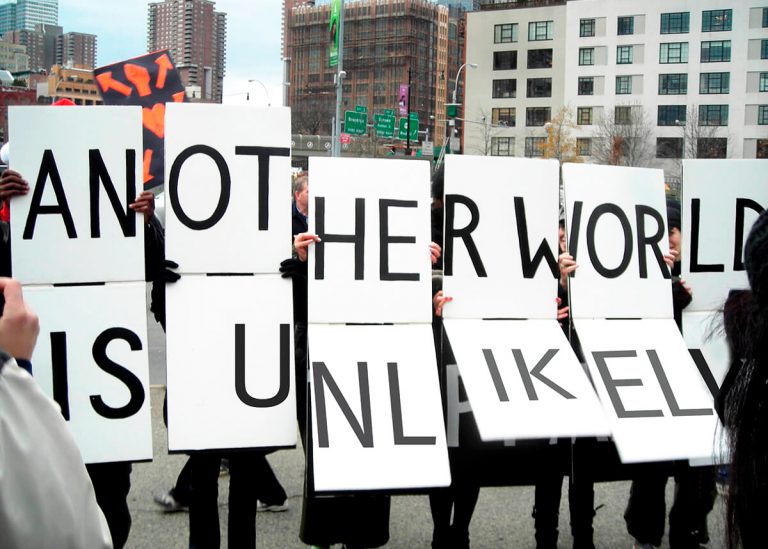

We don’t exist in isolation. We never have. Now we are entering a time where we can no longer live in the illusion of isolation; we can either embrace this new understanding and work with its implications or face the hubris of our inaction. I want to conclude with a call to arms, a call to closely consider our relationships (both human and non-human) with the world within which we live and work. A call to consider ourselves in relationship with, not as masters of, the deeper ecology around and within us. And to embody this in our actions. I will leave you with this quote by the 16th century philosopher Miyamoto Musashi: Think lightly of yourself and deeply of the world.