The year 2020 has birthed many new words. On February 11, 2020, the World Health Organisation gave the world the name of a new disease, COVID-19. The Indian government, as a measure to “flatten the curve”, declared a nationwide lockdown and asked over a billion people to stay at home. The sudden halt of the movement of people, goods, and attendant economic activity disproportionately affected the most vulnerable in our societies.

As the months passed, and those who could afford to continued to stay at home, the newspapers and websites kept a grim vigil of those whom we lost to the virus. The Oxford English dictionary chose not to name a word of the year, instead noting that 2020 saw “seismic shifts in language data and precipitous frequency rises in new coinage.”¹ The Dutch murmured of “huidhonger”, loosely translated as skin hunger. It was a word for our need for human contact, as explicable as, in the words of Margaret Atwood, “a starved dog’s logic about bones”.

It is tempting to think that we are all humans with biological apparatus which is similarly vulnerable to virus attack. Such temptation dissolves in the face of evidence. How vulnerable we are—what armours we buckle on, what ramparts we erect—separates us. We are not all alike; history, human-made institutions and power structures across geographies and cultures make the experience of the virus specific and particular.

Take how the pandemic and the lockdown in India affected different people differently. When Fields of View,² a non-profit research organisation that designs tools to improve public policy dialogue, studied how government and non-governmental organisations in Karnataka, a state in southern India, provided relief to vulnerable groups, the specific and varied impact of the crisis was reflected in the diversity of relief operations. The flow of information observed defied conventional wisdom, which assumes a hierarchical cascade to be the most efficient during disaster relief. The information flowing from decentralized networks of non-governmental organisations proved robust and of greater utility to relief workers. More decentralization, in terms of power and resources, translated into greater resilience.

In a country where phone penetration is high but smartphone penetration is not, an app will not solve the problem. In a neighbourhood where people speak many languages, many dialects, and have different kinds of literacies, asking people to respond to a report in English will exclude many. And then, there’s the tricky part of imagination. The act of planning is not just about what is; it involves what can be, so how can people harvest the fruits of their collective imagination?

Now imagine: in a neighbourhood in an Indian city, a real estate developer and an eight-year-old are playing a game together with the goal of building their neighbourhood. There is a new law that says that apartments more than a certain size have to plan for and install a sewage treatment plant. As the real-estate developer indicates the location of the plant, the eight-year-old disagrees—they want their playground to remain unaffected. The real-estate developer is taken aback—they have never had to have a dialogue with a child. The other participants also need to decide their collective future.

Now imagine: in a neighbourhood in an Indian city are young teenagers who are building their neighbourhood. One of them adds a building and says, “Is building mein sabko job milega” (“In this building everyone will get a job”). No such building exists, but that’s the aspiration and imagination of a young person made concrete. Can the city plan for this young person’s aspiration?

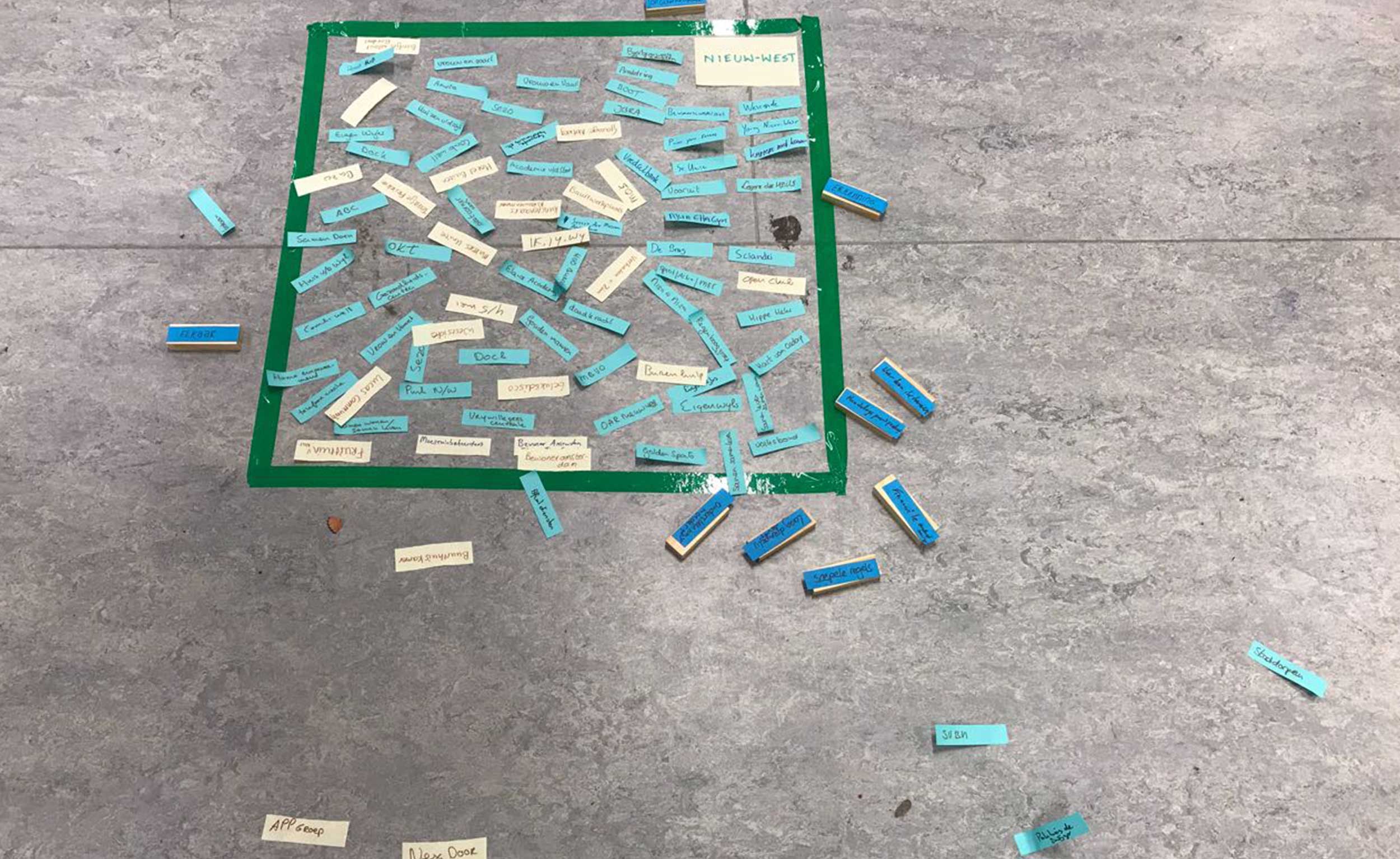

These instances are not fictitious—they are from different sessions of Fields of View’s city game. When it comes to participation, differences in need are based on socio-economic locations and practices stemming from culture and aspirations. The game is a tool that allows people to articulate their different needs and preferences and have conversations about different futures. The game does not involve texts; it is accessible to people with different kinds of literacies. In other words, the game is one way of answering the “how” question—it is a space for people to play, imagine and build a future together. We know of collective nouns, but what we seek to realise are collective verbs, where people actively participate in shaping their world.

Of course, the game is not a magic wand to solve all that festers in our societies—there are power differentials and vested interests. It is not an easy journey to a better tomorrow where everyone participates in shaping the idea of what “better” is. And so, we keep asking, “Have we gone far enough? Can we take a few more steps?”