The Graveyard

In 1995 an art group named Apsolutno investigated the death of two cargo ships in a shipyard of Novi Sad in former Yugoslavia. Two rusted ocean ships were landlocked more than 1000km from the nearest sea. The artists’ forensic study concluded that the ships died under suspicious circumstances: international sanctions, a collapsed economy, war and corruption.

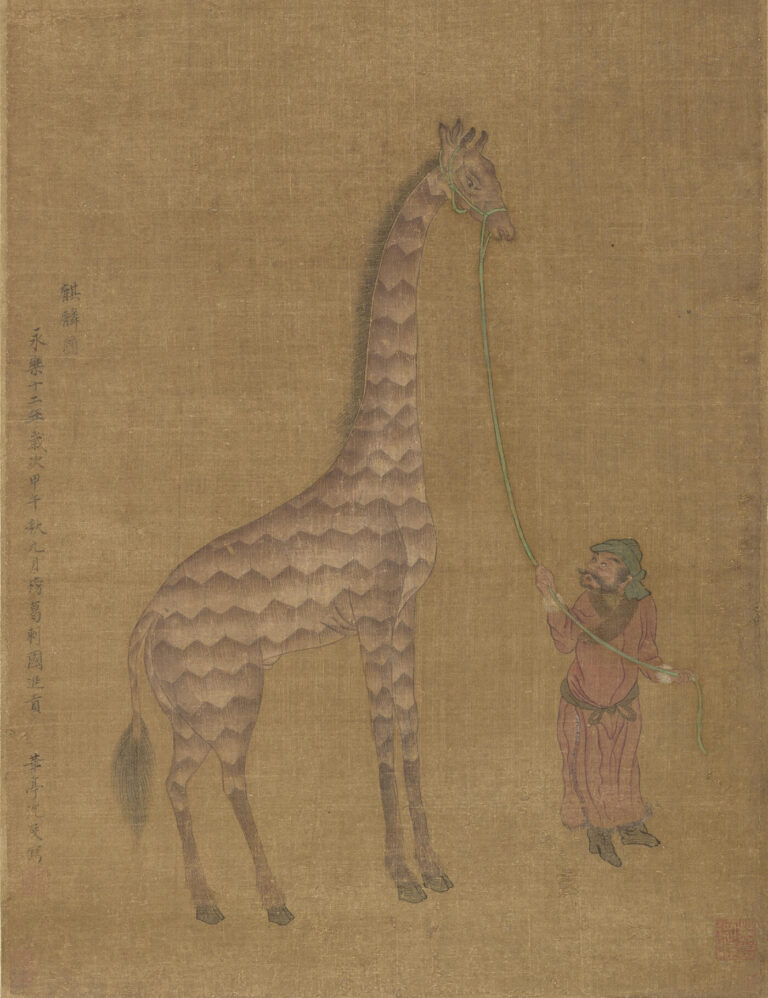

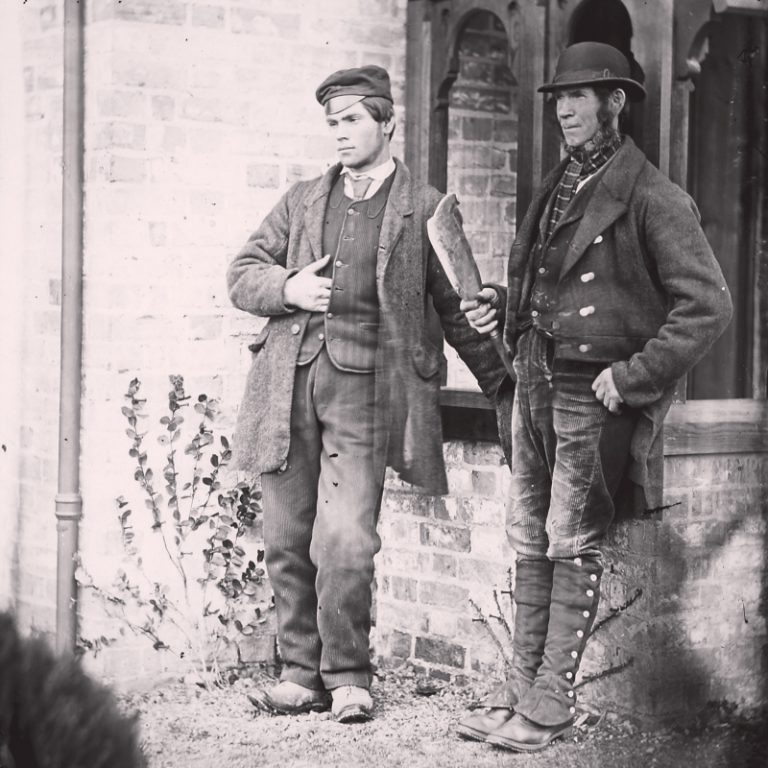

Over twenty years later, we are standing on the shores of the Indian Ocean peering through a camera’s telelens. Three National Institute of Design students approach the Alang Ship Recycling Yard, the largest ship graveyard in the world. Here thousands of massive ocean vessels are dismantled under labor-intensive and hazardous conditions. The ships’ valuable materials are extracted, and the parts resold. Perhaps even the Yugoslav ships are decomposing here.

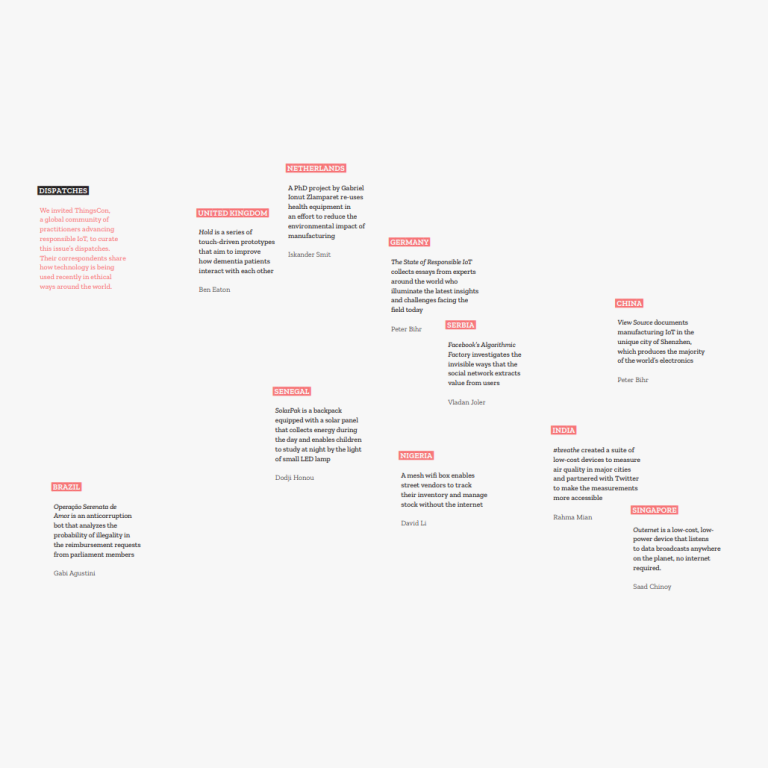

When it comes to the Internet and many things digital, we have a habit of neglecting materiality. The Internet’s infrastructure is hidden from view, buried or behind barbed wire. The same holds true for the shipping industry. This phenomenon even has a name: sea blindness.

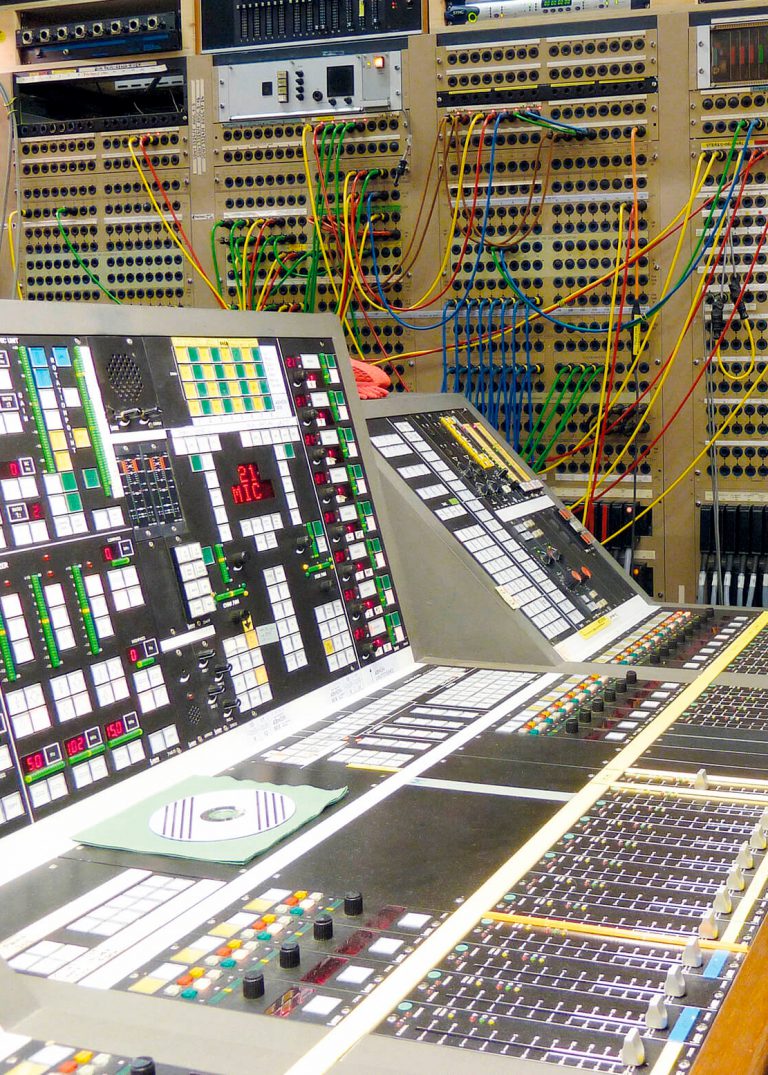

As Share Lab, we conduct investigations into the invisible aspects of the Internet. The mining pits, the metal refining factories, the assembly lines, the data centers, the submarine cable landing points, the algorithmic factories or the shipping graveyards are not meant to be seen by us. This physical infrastructure is supposed to be invisible. It should not disturb the cleanness and joy of the Silicon Valley utopia and its immaterial cloud. Nevertheless, the shipping industry plays a crucial role in our connected devices. That’s why we begin our story with the death of a cargo ship.

Global production was made possible with the invention of one simple object, the cargo container. Marc Levinson explains in his book, The Box, that the shipping container standardized the transportation of goods and led to an explosion of production. 90% of what we consume today is transported by ship. Every Apple device, for example, contains components gathered from 743 locations across six continents. Whilst submarine cables underpin our information society, marine transportation underpins our consumption.

Explosion in slow motion

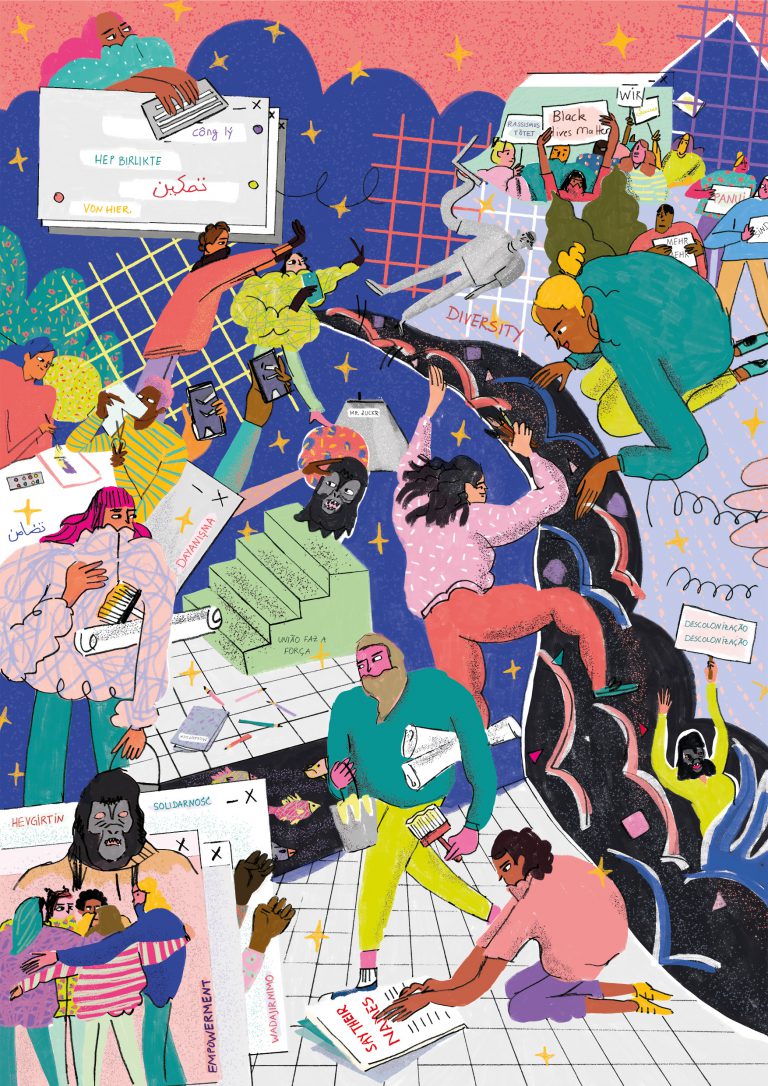

Along the edges of the ship graveyard are hundreds of shops, junkyards and workshops dismantling, sorting and finally selling each piece of the ship. They are conducting a kind of live exploded view. The ship, a complex three dimensional object, is transformed into two dimensional projection of its parts.

Millions of sorted, flat pieces are resold. Everything, from the lifeboats to the ceramics, to the engines and even the cleaning supplies and bed sheets are redistributed. An informal settlement nearby houses tens of thousands of migrant workers. Their homes are made out of available materials – in this case, the parts of huge container ships. A local restaurant serves food on a former ship’s ceramic plates, and a neighbor is laying on a bed once used by a sailor on the North Sea. From the graveyard, these components will continue their new life. What was once furniture on a luxury cruise ship will now become furniture in a hostel, school, or restaurant in India.

Why are these parts being reused? According to one seller from Alang market, “The quality of wood, steel and other base metals used in the ship’s products is supreme. These products are manufactured in developed nations. Moreover products used in ships are of superior quality as they have to sustain for longer period.” This afterlife of things is somewhat unusual in our age of obsolescence. We live in a time when reuse, modification and repair is not encouraged, and in some cases, it is illegal. Many of the consumer products we buy are designed to have an artificially limited life. They become obsolete (that is, unfashionable or no longer functional) before it’s necessary.

Fig 2. E-Waste from cargo ship at Alang beach

Planned obsolescence

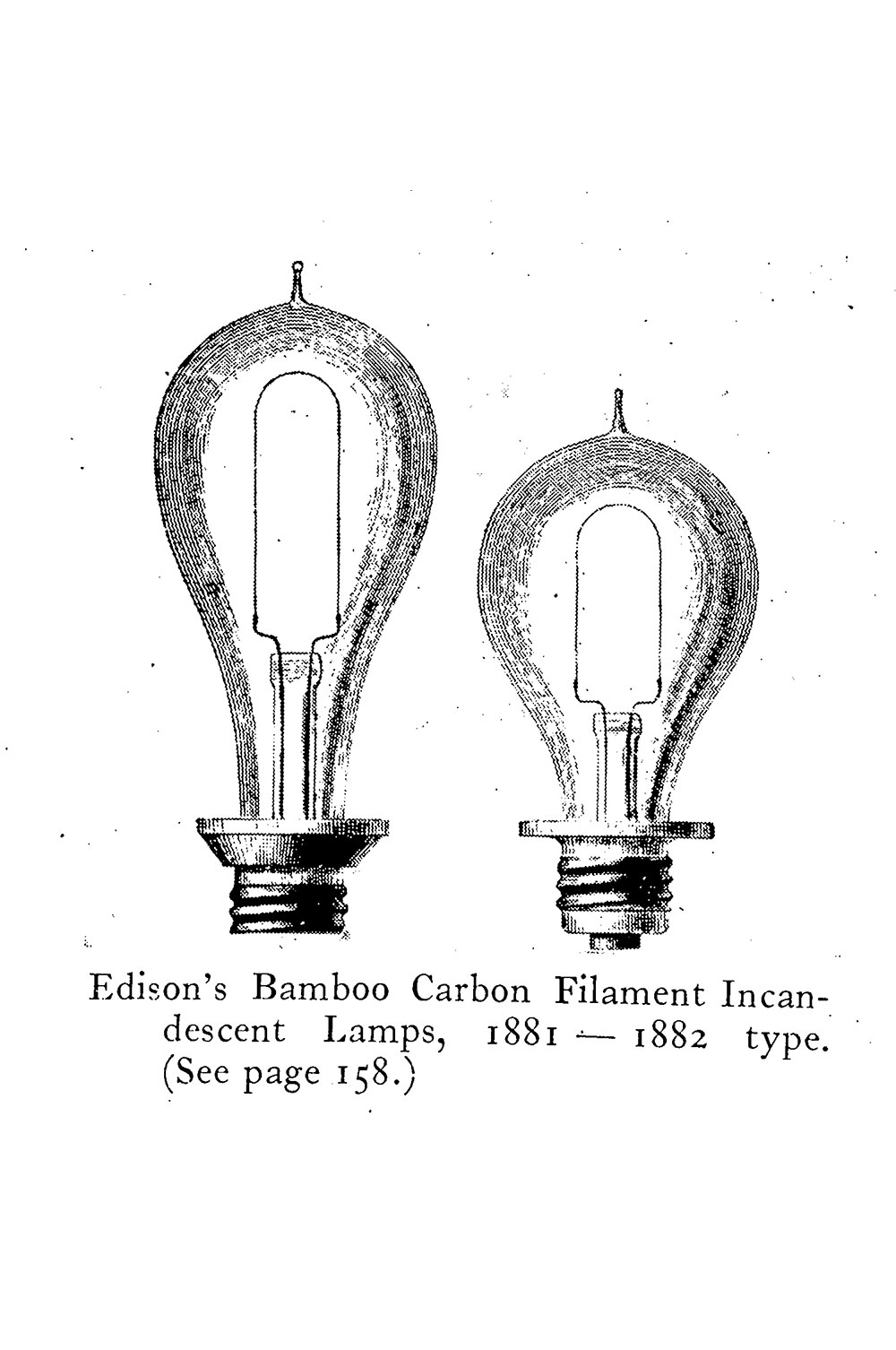

Planned obsolescence aims to generate long-term sales volume by shortening the replacement cycle of product. It was pioneered by a particularly notorious cartel in the 1920s. The Phoebus cartel represented the largest producers of light bulbs at the time, among them Osram, Philips, and General Electric. The main mission of the cartel was to control the manufacture and sale of light bulbs. They intentionally shortened the lifespan of their light bulbs to ensure that none of them lasted more than 1,000 hours, which led to more purchases. The strategy took off and was even encouraged as a method to stimulate the economy after the Great Depression. Aldous Huxley satirized this approach in Brave New World, published in 1932, “Every man, woman and child (is) compelled to consume so much a year in the interest of industry”.

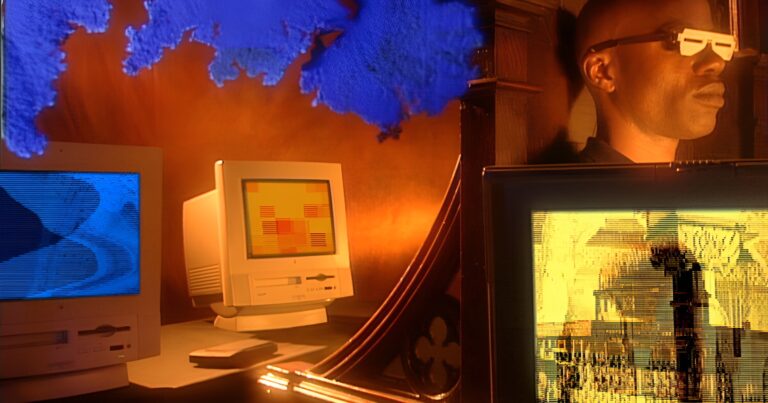

As David S. Abraham points out in his book, The Elements of Power, “We are now on a global trajectory to toss out over a billion computers annually. This is not just because we have more of these devices but because we use them so briefly. The average lifecycle of a smartphone is about 21 months. Likewise, laptops, tablets and many of our hightech gadgets have life spans of less than three years”.

Government-endorsed afterlife

Cuba, a country preserved by isolation and run by the same regime for almost six decades, is conducting a long social experiment against planned obsolescence. Since the 1960s, the Committees of Spare Parts (Comités de Piezas de Repuesto) advocated that workers should not just own their own tools of production, but they should also be able to fix and even create new ones. “Worker, build your own machinery!” declared Ernesto “Che” Guevara. Sixty years later, many objects in Cuba are pushing the boundaries of their original lifespan.

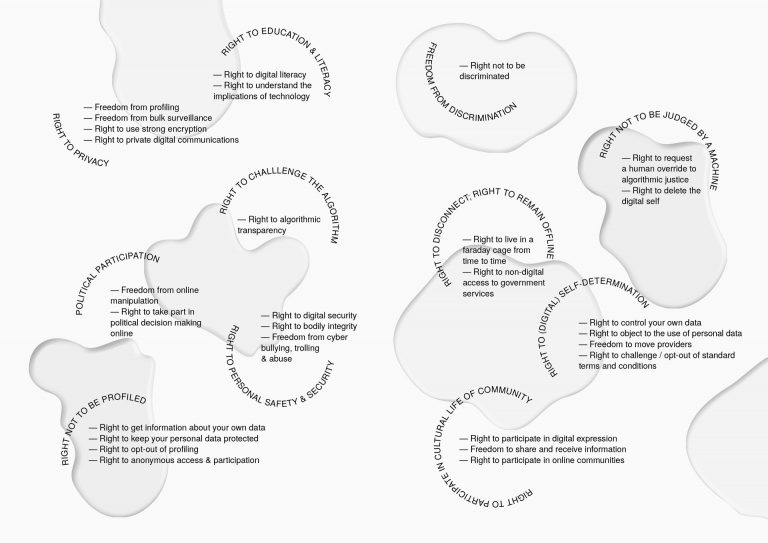

Right to cure devices

Design, whether seen through a socialist or capitalist lens, is always in dialog with economics and material reality. Even the smallest screw can represent the ideology of its manufacturer. Apple deploys a specially designed pentalobe screw in its products since 2009. It is an unequivocal barrier against the owners of the devices; they cannot open, examine or ultimately fix their things.

For Apple and many other technology companies, the idea of ownership clearly deviates from the one depicted by makers, “If you can’t open it, you don’t own it.” Increasingly, we don’t even buy our devices. Instead, we lease them, such as with two year phone contracts or IoT devices maintained by monthly payments. Companies introduced restrictive licensing agreements that bar users from fixing hardware or software themselves. In these situations, the real owner is the company.

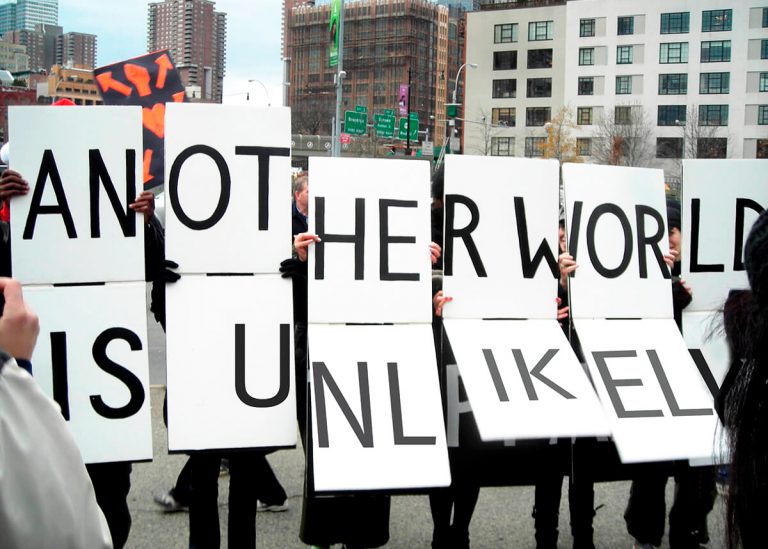

To conclude, I would like to draw the line from the death of objects and planned obsolescence to a possible future called the digital dark age. Much of our data today is hosted by Fortune 500 companies. And these companies have their own lifecycles. Using a statistical technique called survival analysis, a group of researchers discovered a company’s mortality rate. A company’s risk of dying has nothing to do with how long it had already been in business or what kinds of products it produced. Regardless of what industry the company is in, the team estimated that the typical company lasts about ten years before it’s bought out, merges, or gets liquidated.

Else it will all too quickly end up in a landfill graveyard.