Like all other things, art senses the passing of time. Paint becomes dry and flaky; bronze gets tarnished and corroded; fibers and fabric get thin and tattered and may be attacked by a variety of insects; marble breaks and cracks; resins and plastics become yellow, brittle and cloudy. Dust, grime, and grease—not to mention stray hairs or microscopic bits of food—accumulate on surfaces, sometimes for centuries, before being cleaned. The condition of a work of art often tells a compelling story of time not only as a material, but also as a political and social condition. A tear in a painting might have been caused by the butt of a rifle belonging to a Nazi officer invading a house.¹ Moth damage to textiles might be discovered only in the occasion of the piece’s removal from storage, years after the infestation began and when the piece is already damaged beyond repair.² A piece of public art might be removed, possible damage notwithstanding, from the place it was conceived and commissioned to be in, as a result of increasing political hostility toward its message.³ Another piece of public art might be expressly designed to be demolished, materialized only for a brief moment before ceasing to exist in all but images and memories.⁴

A meditation on how time leaves imprints on artwork must, of course, consider materials: some, like steel, marble, or bronze, are hardier than others, like loosely woven fabrics. There is, too, the issue of medium: the (ostensibly) ephemeral nature of performance art pitted against the (ostensibly) hardy nature of sculpture. And there are the questions of technique and technology: applying additional layers of varnish or lining meant to protect a painting for centuries to come can backfire spectacularly just decades later, when they turn out to worsen the very damage they were trying to prevent.5 In their own particular ways, artists and art conservators are like disembodied time travellers, projecting the artwork toward a time that they will not be able to see—or foresee. A gift to the future; a performance of persistence.

Yet there is more to be extracted from this idea of persistence than a mere consideration of material, medium, or techniques and technologies. Persistence can describe the continued or prolonged existence of something, but also indicate a continued course of action in spite of adversity. Though seemingly simple, these meanings multiply across contexts; persistence—or the ability to persist—is not to be taken for granted. It is not an aspirational platitude. For some, persistence can be a battle; an ongoing, hard-won struggle against the blunt end of the necropolitical—that is, the structures of power that determine who may live, and who must die (Mbembe 2003). The production of death as an enactment of power isn’t limited to the body; it encompasses affect as much as it does flesh.

Bodies deemed disposable by the necropolitical order produce art deemed equally disposable. It is not coincidental that the artwork that persists through time—and that can, thus, be projected towards the future—is most often produced within a specific set of constraints that make its survival, and that of its creator, guaranteed within the necropolitical order. In designing an artwork meant to exist for years, decades, or even centuries, the artist projects something toward the future, but this materialization of affect does not occur in a vacuum. Having access to time, space, funding, and materials—amongst other factors—is fundamental to the persistence of both art and artist.

Necropolitics—a noun to which I am tempted to add the adjective ‘colonial’ not because Mbembe failed to address the relationship between the two, but as a reminder of the strength of this link—was, and continues to be, a force that shapes the presents of art and artists of color. The loss of art is a loss of the ability to conceive persistent presents, pasts, and futures. Time is a fragile thing; gaps and voids lead to cracks in the surface of life that might never be bridged again.

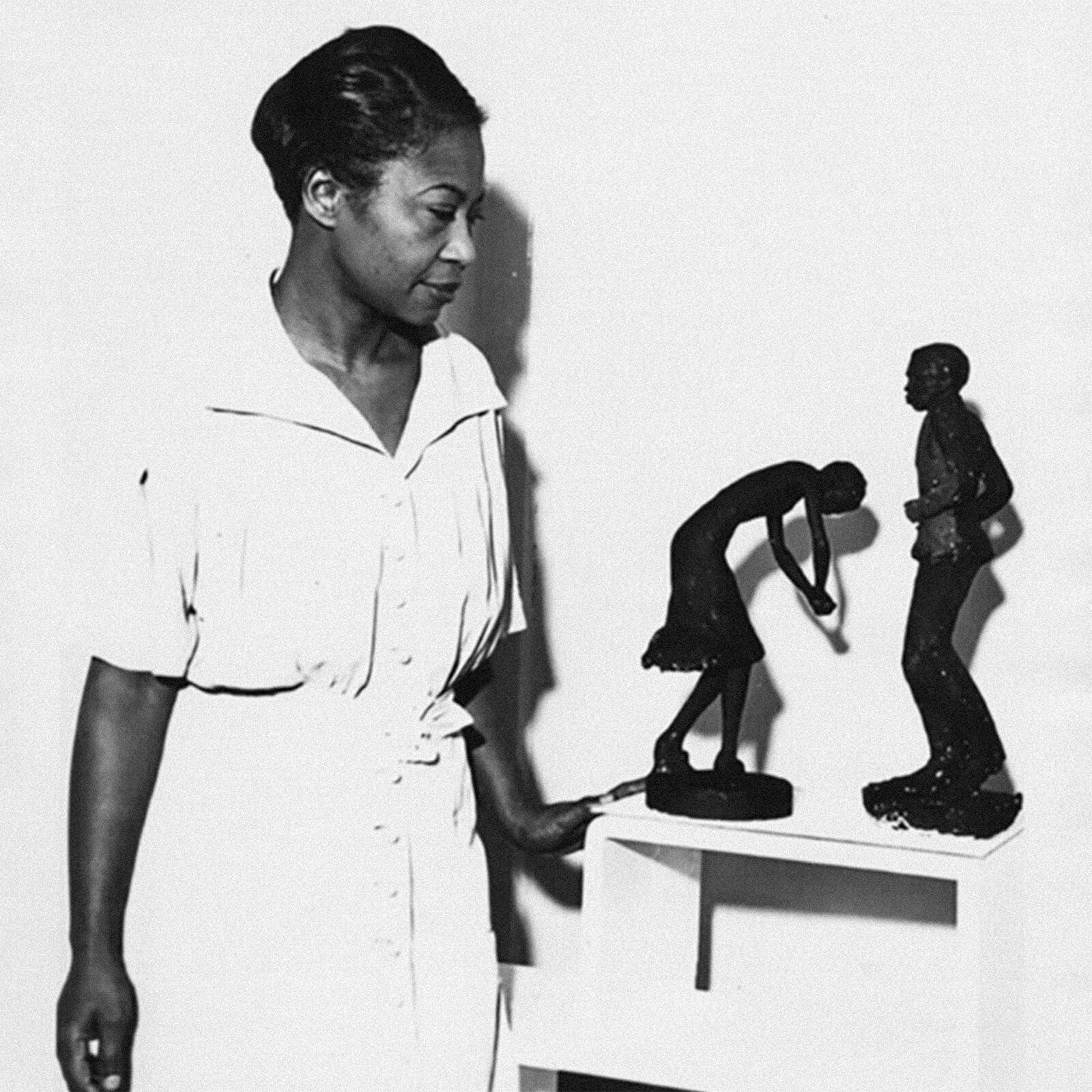

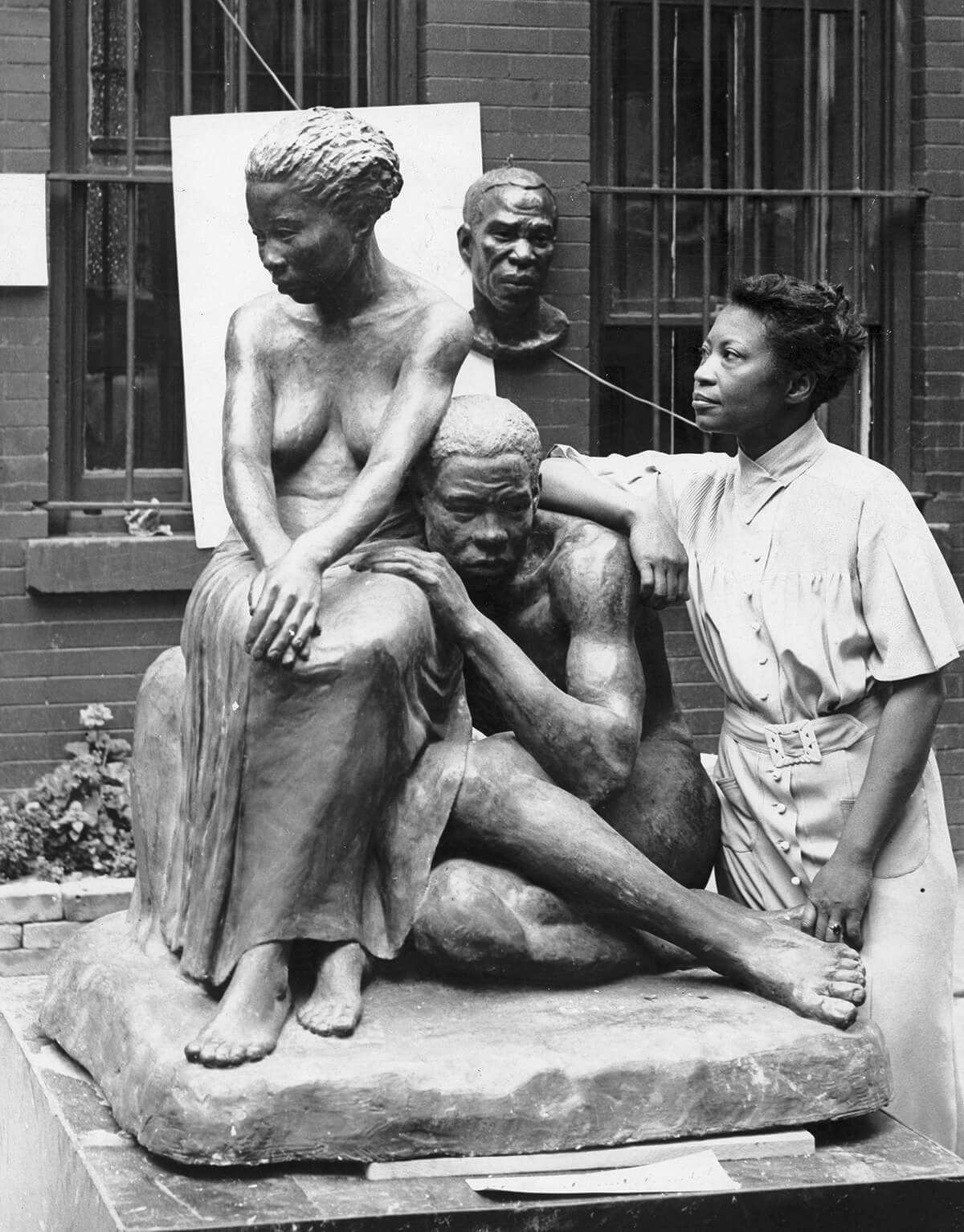

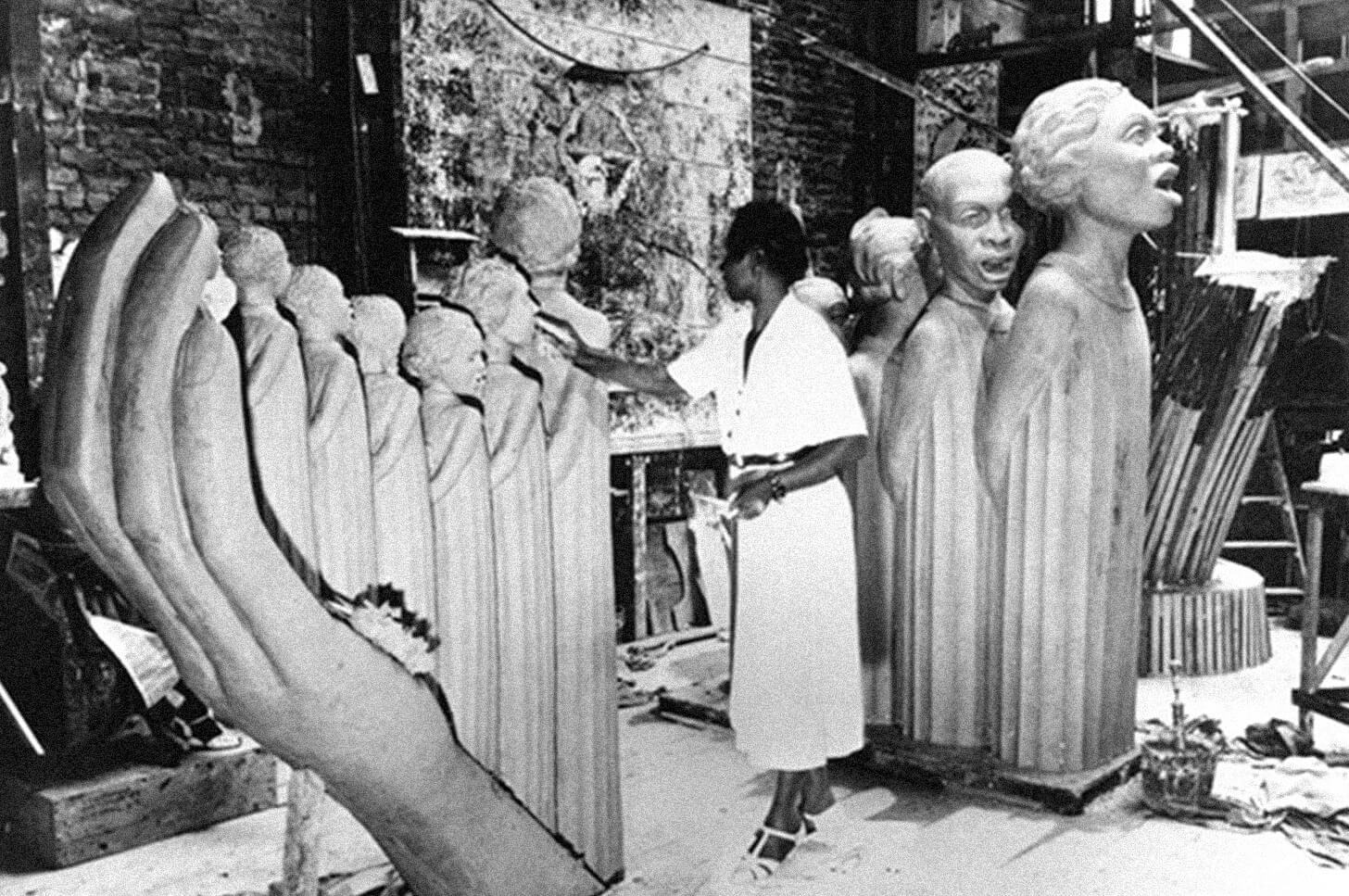

The life and work of African American sculptor Augusta Savage is an instance of how necropolitics, in defining those who get to live or not, On Persistence: The Past Art/Works of An/Other Future Luiza Prado also defines whose artistic manifestations persist. Born in 1892, Savage was a key figure in the Harlem Renaissance—an artistic, intellectual, and political movement that spanned the 1920s and had profound repercussions in African American culture. Her trajectory was marked both by her exceptional talent, and the extraordinary nature of the challenges and struggles she faced. From enduring whippings from her father as a child due to her interest in art to completing a four-year course at the Cooper Union in only three years,6 Savage was nothing if not persistent; yet this tenacity did not guarantee the survival of her body of work. Savage worked most often with plaster and clay—two friable, fragile mediums, most commonly used for creating the first molds for pieces that will be later cast in hardier materials, such as bronze. Typically, however, Savage’s clay and plaster sculptures were finished pieces, rather than prototypes—not due to a calculated desire for ephemeral or impermanent work, but due to the high cost of bronze casting. As a result, works like “Lift Every Voice and Sing” (also known as “The Harp”), commissioned for the 1939 World’s Fair in New York City, were destroyed after exhibition, for Savage did not have the funds or space to store the sculpture, nor to have it cast. Of the piece, only photo and film documentation—and perhaps some of the small metal souvenir copies sold at the fair—survive.

Granted, not all of Savage’s work was lost to the necropolitical mechanisms of financial instability, systemic racism, and gendered inequality. “Gamin” (1930), one of her most famous pieces, is currently part of the collection of the Smithsonian African American Museum. At first sight, the bust might look like a bronze cast; at closer inspection, however, the piece reveals itself as another example of her plaster sculptures, the young boy it depicts cleverly shaped and painted to resemble the texture and color of bronze. If in a way it is beautifully fitting that this sculpture—an early work that won Savage a scholarship for a period of travel and study in Europe that helped shape her career—is one of her few surviving pieces, “Gamin” also bears witness to the massive gaps left by the loss of her art. This is a piece that speaks of itself as much as it does of far broader structures. Is it perhaps the accumulated, compressed weight of centuries of inequality that shapes the enigmatic expression of the boy? Or, most poignantly, is it the prescience that, against all probability, this bust will withstand the test of time, elements, and systemic adversities to persist and expand possibilities towards futures unknown?

1. instagram.com/p/BmlgWpugJrA/?taken-by=baumgartnerrestoration

2. tate.org.uk/context-comment/video/lost-art-joseph-beuys-felt-suit

3. hyperallergic.com/463819/on-day-of-german-unity-city-of-kassel-removes-artists-monument-for-refugees

4. artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-rachel-whitereads-house-unlivable-controversial-unforgettable

2. tate.org.uk/context-comment/video/lost-art-joseph-beuys-felt-suit

3. hyperallergic.com/463819/on-day-of-german-unity-city-of-kassel-removes-artists-monument-for-refugees

4. artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-rachel-whitereads-house-unlivable-controversial-unforgettable