Here, I present to you a painting of a pet giraffe brought to Bengal in 1414 by envoys from the Malindi Kingdom, in present day Kenya, where it was entrusted to Zheng He, a well-known mariner, who took it to China as a tribute to the Chinese Emperor Yong-le ¹.

Together, the painting and the lost story of the giraffe raise questions around provenance, collections and technology (a novelty like a pet giraffe) that are relevant today. While much has changed since the painting was made, the colonial logic which has driven the commission and acquisition of art, and infused its history, is constant. The painting of the pet giraffe is one of many objects sitting in tranquil silence inside glass cases in museums around the world. Ancient porcelains in pristine condition. Lavish oil paintings with ornate gold frames. Contemporary art objects with subversive but obscure messages. What brought them here? What keeps them here? And where do they want to go?

Extraction – Displacement – Isolation – Domination.

These methods of cultural colonialism have been practiced for centuries. They are effective because, like slavery’s “long process of dulling,”² they blunt the soul with repetition. In resisting the power of art history – specifically, the crushing weight of its scholarship – can we bring the smudged outlines of art history into focus? Can we sharpen the edge of contemporary art to a keen point? I’m hopeful we can bring incisive new ideas to the question, If you were a giraffe, where would you like to go?

Gold bar for the lady

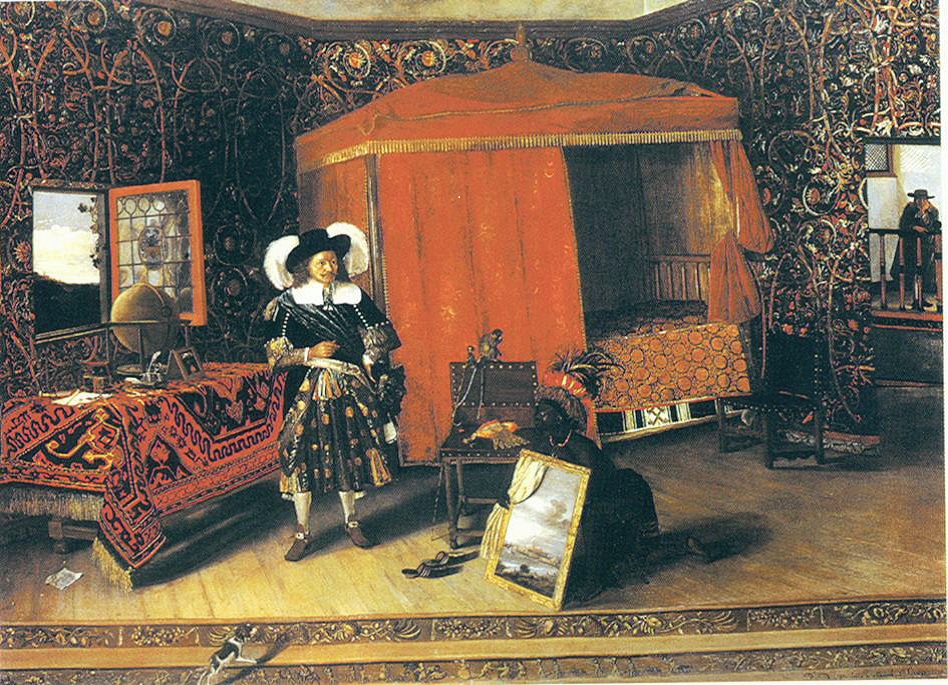

In an essay on the painting⁴, art historian Amy Knight Powell notes that even as Director General of the company, Wilre, who was born to a lower class family and began his career as a smuggler, continued to covertly send gold to his wife in the Netherlands. “Capital,” she writes, “made everyone who was not a capitalist in this context into a beggar or part-time crook.” The Dutch West India Company itself began as an organized criminal operation before becoming dependent on subsidies after a treaty was signed with the Spanish and Portuguese. The African’s identity is unknown.

These colonial-era paintings serve as a record of the lives and aspirations of the people powerful and wealthy enough to commission them. How then did Western, popular art history respond to these works in the twentieth century?

The Named and the Unnamed

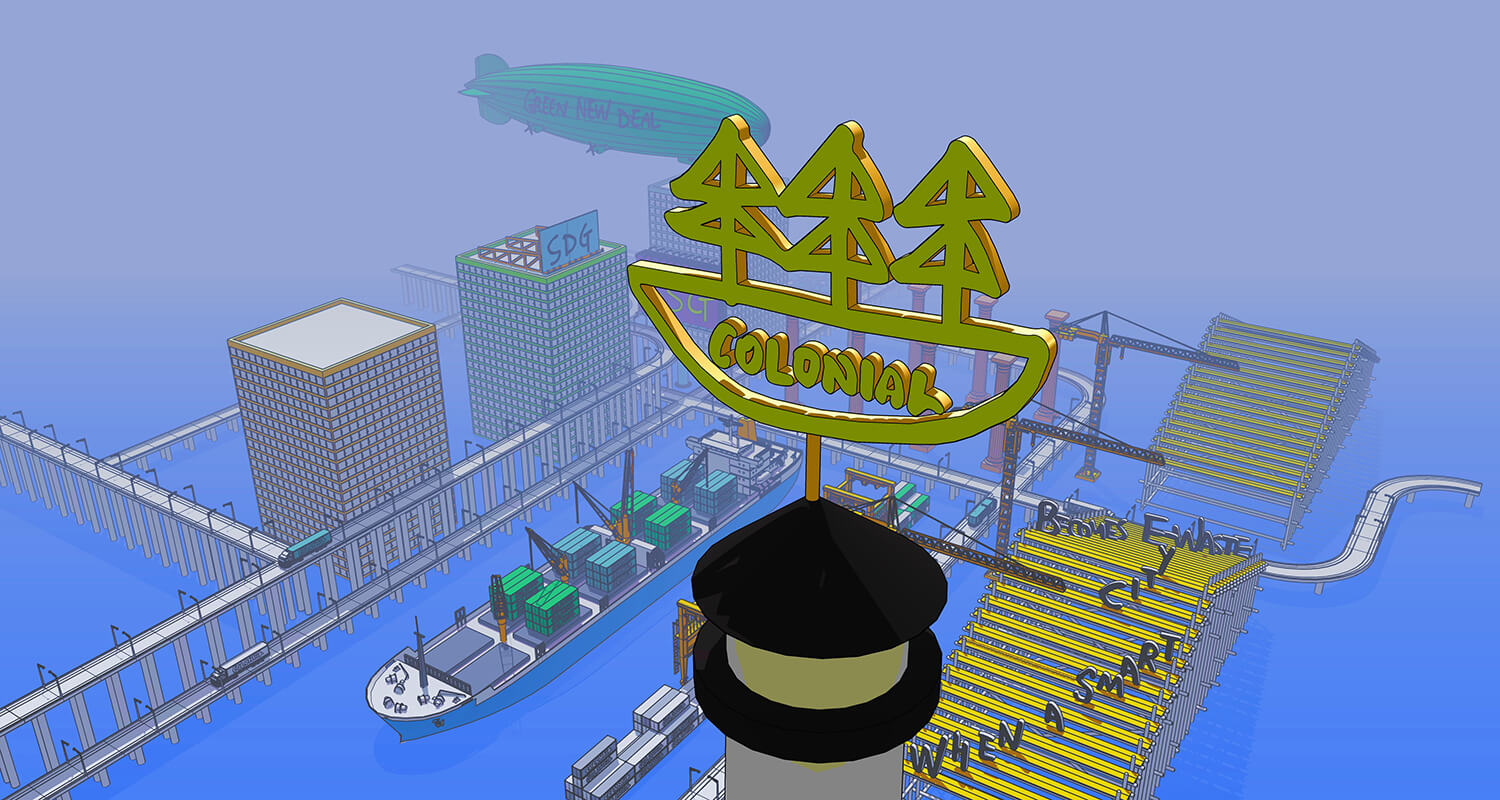

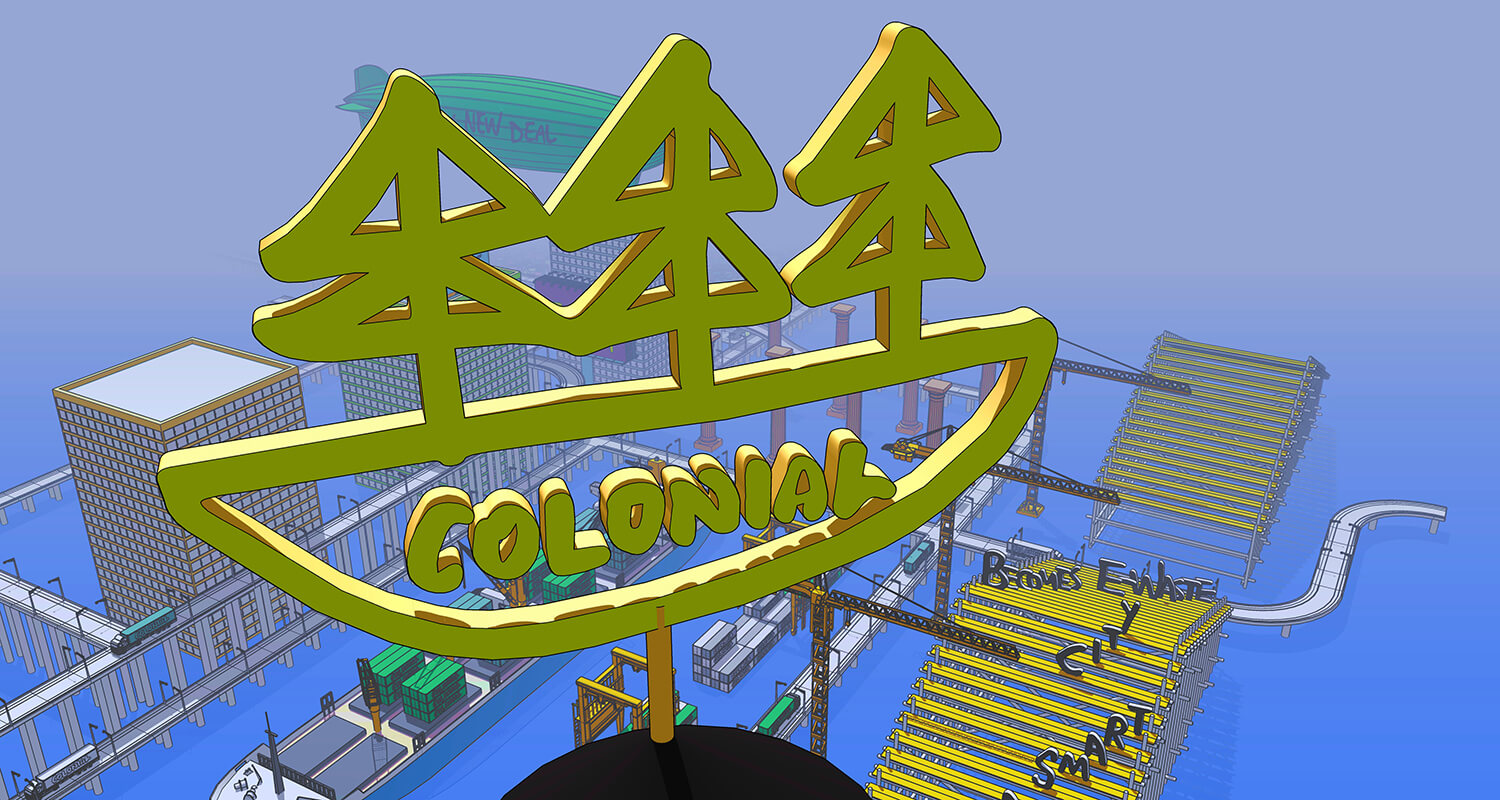

Returning to the second painting of Dirck Wilre for a moment, I believe it’s immensely important that we understand the individual figures in the paintings. After all, Dirck Wilre’s power and wealth were directly related to his capacity to commission the painting. His life, and those of other colonists, materially affected the lives of the people – past and present – in the lands they helped colonize. Even today, the legacy of giant operations of the Dutch East India Company and the Dutch West India Company continue as the many successors they inspired, joint-stock companies and startups with global operations.

History without accountability is pure decoration. Decolonization begins with transparency and accountability. To practice decolonial art history and art, we need to examine the role of the art object. Inside ‘Portrait of Dirck Wilre in the Castle of Elmina,’ there is a painting, held by the unidentified African, that offers a visual clue to the true force underneath the surface. As Powell writes, “the painting–within–De Wit’s–painting conceals the person who presents it, as an illusion of deep space, but it does something more violent, opening the semblance of a white hole in that person’s flesh.” Powell asserts this knotty allegory might best be described by Cedric Robinson’s term, “racial capitalism”.⁶

Implicit – Explicit – Complicit

First, we must acknowledge the complicated relations between the colonizer and the colonized. In a simple binary, these terms inadvertently produce abrasive reduction and reproduce the colonial mindset, rather than forging meaningful paths toward decolonization. Underneath the binary, there are messy realities of complicities and dependencies. The oppression of peasants and workers in Europe relates directly to the transatlantic slave trade and the violent expansion of empire, where colonists built supercharged replicas of the old-world order. Moreover, examining the complicated, nuanced complexity of racial capitalism draws attention to the local capitalists in the Global South who maximized their opportunities during the colonial period. As both oppressed and oppressor, they embody the duality of colonialism within their identities and bodies. Their political alignment with the colonizers was instrumental in realizing and legitimizing systems of exploitation long after the initial violence enacted by the colonizers. Local capitalists continue to enable new forms of colonialism in the Global South today through massive debt-financed, multinational developments. The binary between the colonizer and the colonized fails to represent the messy contingencies that many of us are involved in.

How did technology enable colonialism? And how does it capture the imagination of new capitalists? The exploitation and disenfranchisement that was transposed from Europe and replicated in extreme forms, on massive scales, across colonized lands could only take place with the help of new or newly modified technologies. Early computational technologies such as accounting, book-keeping and transatlantic communications were critical tools for centralized control which enabled slavery and colonial enterprises. Their practices and assumptions persist invisibly to this day, shaping our present worlds. Smart Cities in the Global South are clear examples of how computational technologies, societal control and debt-financed developments bring together new forms of political, economic and military dependencies.⁷

Can technology offer a solution to the problems it helped create? Among the tech-activist circle, there is high interest in decentralized technologies, especially regarding alternative web protocols that promise more democratic control or collective stewardship. Decentralized technologies on their own are not inherently egalitarian nor necessarily empower the oppressed.⁸ They can be used to further white supremacy, intentionally or unknowingly. Because of this, it’s important to recognize the contemporary efforts of scholars and activists defining and practicing decolonial computing.⁹ They break with the past to create decolonial practices for the future. In this way, instantiating decolonial futures for the new world has always necessarily thrown questions about the old world into relief. What can we do now with the resources and insights we possess today to prevent further damage and bring a sense of correction in the paths of human progress?

To answer the initial question, Where would you like your pet giraffe?, I need to address both complicated histories and complex present conditions, including the presence of Asian capitalists in Africa and those expanding their foothold across the Global South. As an Asian person, as an artist, as someone who’s adjacent to the technology industry and academia, my complicity in structural racism and capitalism, specifically via the philanthropic and nonprofit funding I work with, is something that I work in acknowledgement of, but think about with a commitment to change. Regarding that commitment, our initial questions of the art objects, What brought them here? What kept them here? What ones have been lost? And where do they want to go? may be rewritten as, What forces of power, history, and authority keep them in their place? How might those lost objects’ stories be imagined? And if these objects could walk, where would they go? If you were a giraffe, where would you like to go?

1. Ken Eschner, The Peculiar Story of Giraffes in 1400s China, Smithsonian Magazine, 2017

2. Octavia E. Butler, Kindred (Boston: Beacon Press, 2003).

3. The art historical references in this essay were inspired by teaching ‘Socially Engaged Art’ at the Yonsei Univerity Department of Sociology in the Spring of 2023. I thank my students for their engagement and feedback.

5. John Berger, “Chapter 5.” Chapter 5 of Ways of Seeing by John Berger. Accessed September 19, 2023.

6. Cedric J. Robinson et al., Cedric J. Robinson: On Racial Capitalism, Black Internationalism, and Cultures of Resistance (London: Pluto Press, 2019).

7. Taeyoon Choi, “Colonial Programming”, THIS TOO, IS A MAP, AN ANTHOLOGY, ed. Rachel Rakes, Sofía Dourron (Miami, 2023).

8. Taeyoon Choi, “Racial Justice in the Distributed Web.” Distributed Web of Care, January 11, 2019.