If I’m all right – you ask.

“Well,” I say, “what does that even mean anymore? Aren’t we just trying to cope as best we can? Everything seems so uncertain that for some time now I’ve stopped dreaming. What good is it anyway… All I can see is the radical undoing of the future. One by one, voices are erased from the public stage, leaving behind a jarring emptiness.”

Our eyes meet for just a second, fleetingly, before you tell me that it is not all empty space.

You describe to me entries that you saw online on the Archive of Silence [1]. You recount the stories of cancelled, banned, de-platformed persons – instances of silenced voices, directed at Palestinian advocacy in Germany. Yes, you continue saying, each entry testifies to the waves of erasure and violence and represents the narrowing of public space. But together they form a record that seeks to hold those institutions accountable for their complicity in discriminatory logic.

I notice a change in tone when you assert that their virtuality is not an absence altogether, but that their presence and the conditions of visibility have been altered.

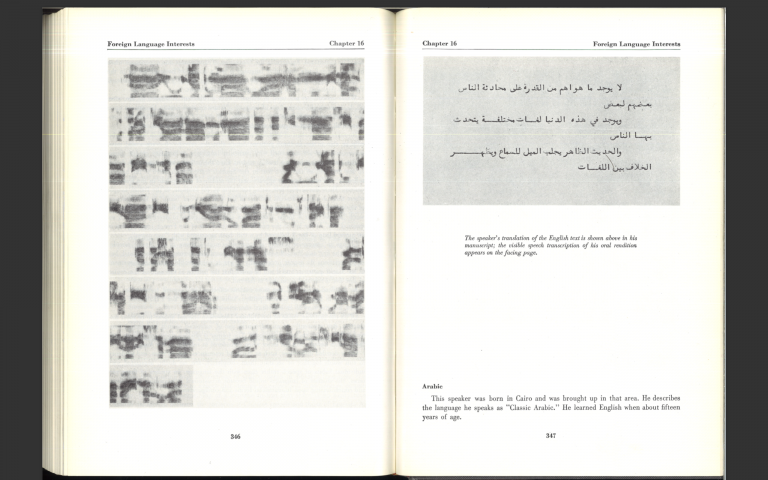

We talk about what these entries now represent. Testimony is usually conceived as an oral-aural event grounded in the acts of speaking and listening, where the presence of a listener is the precondition for validating the spoken testimony. This dimension situates testimony within an embodied, interpersonal exchange, emphasising its dependence on the immediacy and relational dynamics of voice and hearing.

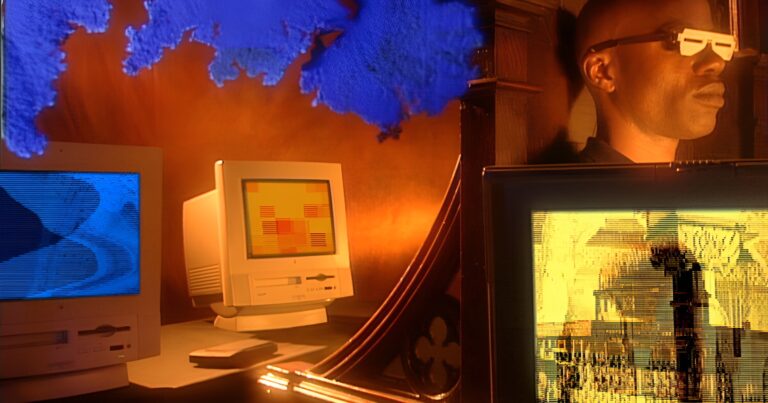

In contrast, these testimonies are shared as a written account on the Archive’s Instagram page, which transforms the speech act into a visual engagement, where the act of seeing replaces the immediacy of hearing. Here, the speech act turns into a looking-relation [2], with testimonies perceived through word-images. You emphasise that each entry on the digital page, each post, acts as a visual marker, thus reasserting themselves in space.

As the entries become more numerous, the testimonies expand their presence within the digital archive, no longer isolated events. In creating a continuous thread, they claim a durational presence. The individual account becomes part of a broader record, chronicling not just singular experiences but exposing the systemic nature of discrimination and the mechanisms of silencing that perpetuate it.

Shared online, these testimonies become visible to anyone who finds their way to the page. Yet, even in this solitary act of viewing, the gaze is implicated in a broader collective witnessing. It is through this enduring visibility that they resist being forgotten, and offer a platform for solidarity. Through the act of looking, and looking again, the entries encode themselves into the virtuality of the viewer’s memory. Viewing thus becomes a commitment to carry these voices forward.

There is a pause.

Glancing at each other, I cannot hold your gaze. My eyes dart away, seeking refuge in avoidance, afraid you might glimpse my fragility. A blink – swift and instinctive – shields my inner self, closing you off from the vulnerability I cannot bear to reveal, breaking the moment we shared.

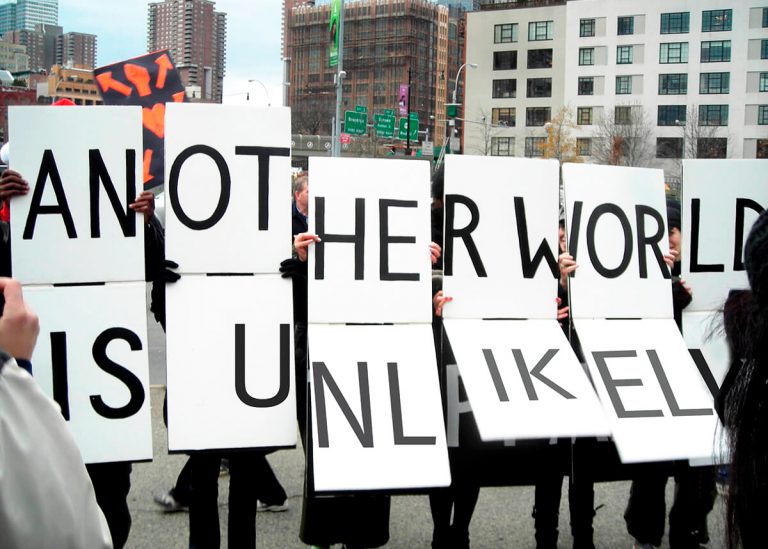

“I’m still worried about what the future holds,” I say quietly. “The Archive of Silence undoubtedly represents a form of resistance and protest. Yet the struggle for a more inclusive future here seems tethered to the pursuit of recognition. These acts of silencing are, indeed, discriminatory and rooted in systemic racism, but even in the demand for acknowledgement, the framing of these injustices seems to remain constrained. It seems bound by the very systems of power that enact the silencing, filtered through their frameworks and vocabularies.”

After brief contemplation, you respond that the struggle for having injustices recognised is one trajectory of resistance. You ask me to consider another. What if, you propose, I would set aside and liberate myself from those external gazes for a moment? You ask, what would happen if I allowed myself to dream freely, unburdened by the scrutiny of others? What would I long for in the quiet of my own thoughts? What kind of world would take shape in the expansiveness of that dream?

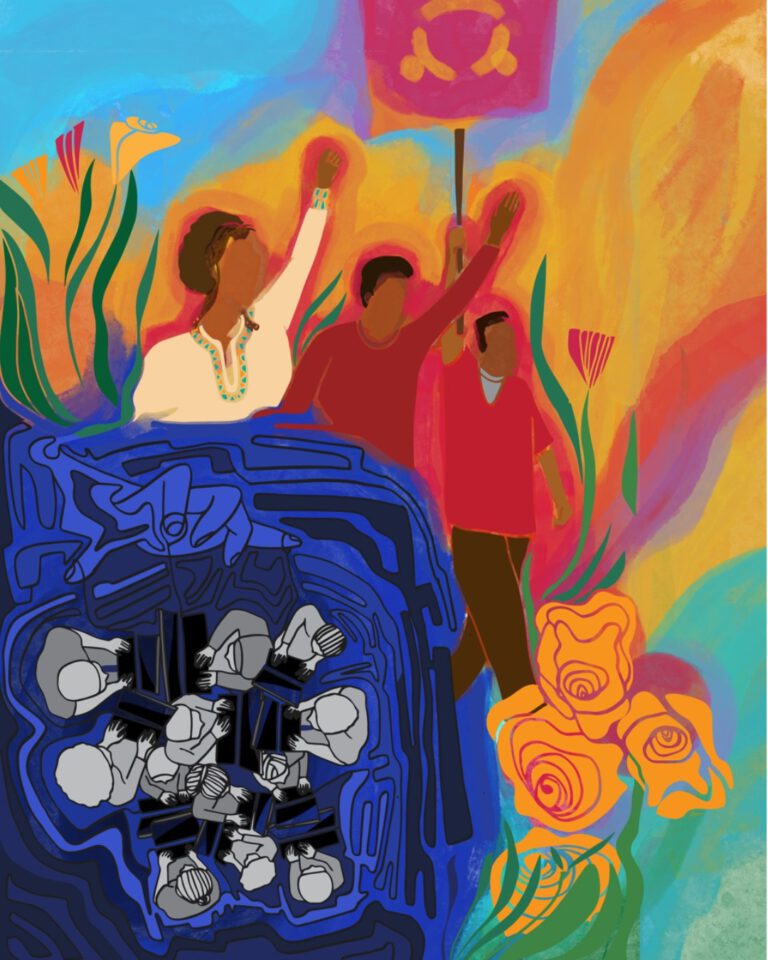

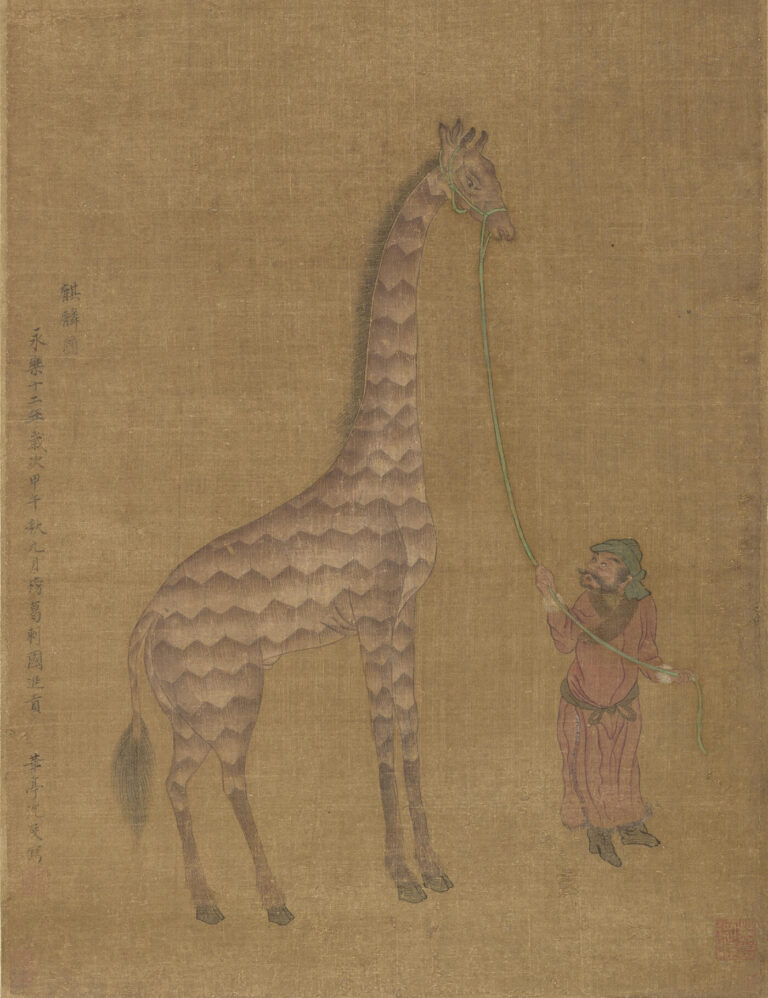

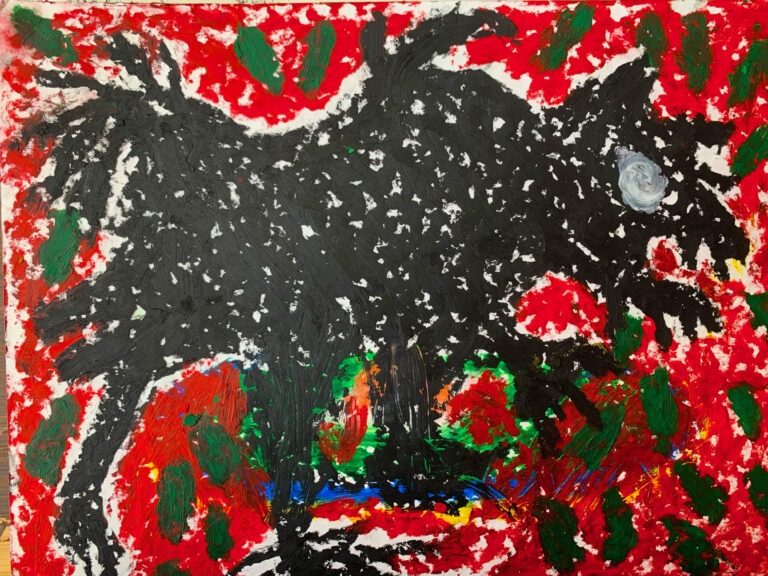

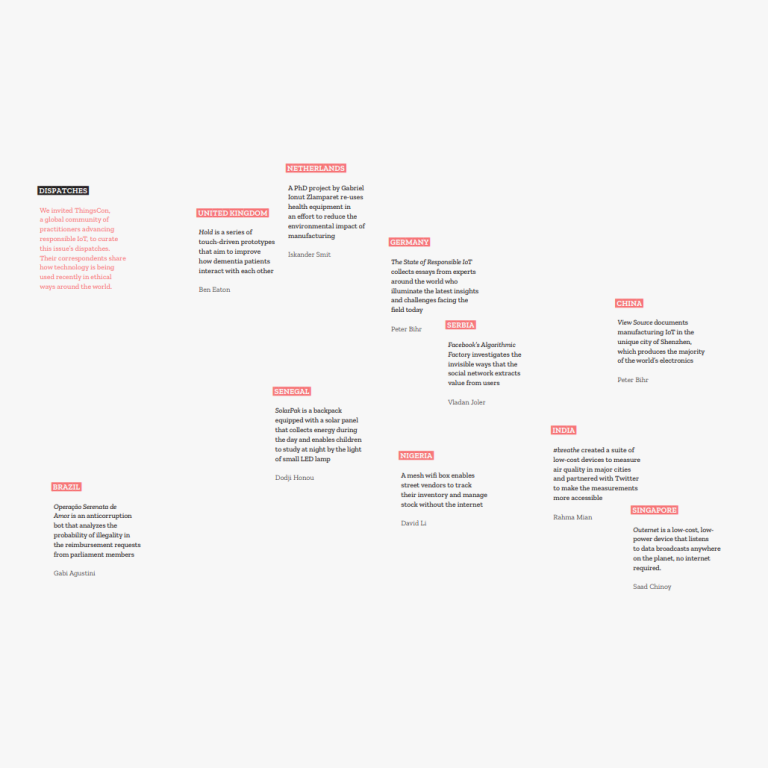

You describe to me works you have encountered in the digital archive of Muslim Futures [3]. These are varied accounts, each offering representations of Muslimness that explore what it means to be visible on one’s own terms. These works reimagine identities to craft transformative worlds, free from imposed narratives of marginalisation and racism. While they acknowledge erased pasts and the injustices that continue to shape the present, their speculative visions create pathways for reimagining existence as diverse, empowered, and centred. In this way, these perspectives are not primarily confrontational. They emerge from introspection, fostering self-recognition and agency rooted in a shared cultural heritage. This inward view becomes a point of departure.

Browsing through the works in the digital archive of Muslim Futures, I am drawn into a different sense of time – one that expands beyond linearity, leaving space for intergenerational presence and the divine. The speculative futures here are grounded in diasporic histories and spirituality, reclaiming time as a domain for imagining liberation. Here, the past is not a site of violence alone, but also of resilience and knowledge, forming the foundation for futures untethered from the exclusionary views of others.

Through this lens, the works of Muslim Futures foster a temporal and aesthetic openness, making room for dialogues between generations, between the earthly and the divine, and between memory and possibility. They carve out spaces where new narratives can emerge that affirm life, resist erasure, and celebrate the multiplicity of Muslim identities as they exist, and as they could become.

So you turn to me with a glimmer of provocation in your eyes, and say that imagining the future can, in fact, be such a radical act.

Your words echo in my mind, and I respond hesitantly, “I wish we could create the conditions for such dreams to become encounters. Where the unknown could be seen for its infinite possibilities. In a place, perhaps, where these fragmented perspectives could be shared and expanded.”

My voice trails off, and I glance at you, wondering if you, too, can see this place taking shape. This time, our exchange of looks feels somewhat different. My gaze engages yours, and you return it. It is no longer the one-directional glance, cut off instantaneously to shield against scrutiny. There is reciprocity, a mutuality that carries weight. It is a look with a double beat [4].

And in this moment, I realise that the responding glance you offer is, in some way, my own gaze returned to me, however, transformed. Your gaze becomes a prism through which my initial look is altered, now holding your history, your beliefs, and containing the memory of all that we just shared. My sense of presence is interrupted by yours. In this way, my gaze folds back on itself, carrying within it the trace of your being, a fragment of your presence now becoming part of me. It is with this expanded sense of being that I carry on looking ahead, through the ongoing struggle.

Endnotes

1. Archive of Silence, Online: www.instagram.com/archive_of_silence

2. After E. Ann Kaplan, Looking for the Other. Feminism, Film, and the Imperial Gaze. London, Routledge 1997.

3. Archive Muslim Futures Now, Online: muslimfutures.de/archive-de

4. Inspired by: Edward S. Casey, “The Time of the Glance: Toward Becoming Otherwise”. In: Elizabeth Grosz (ed.), Becomings. Explorations in Time, Memory and Futures. Ithaca and London, Cornell University Press, 1999. pp. 79 – 97.