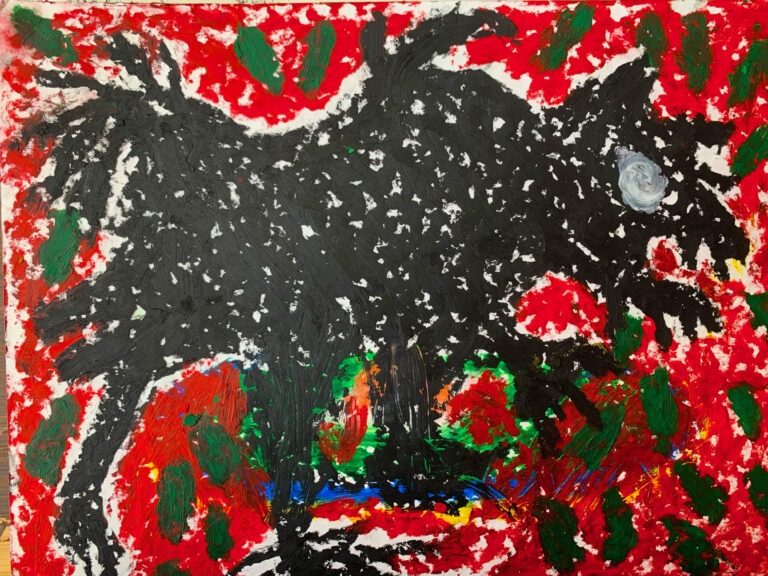

“Let not the sorry plight of the garden upset the gardener;

Soon buds will sprout on the branches and like stars glitter.

Weeds and brambles will be swept out of the garden with a broom;

And where martyr’s blood was shed red roses shall bloom.

Look, how russet hues have tinged the Eastern skies!

The horizon heralds the birth of a new sun about to rise.”

— Muhammad Iqbal – Answer to the Complaint (Jawab-i-Shikwaa),

translated by Kushwant Singh, 1909, Lahore, now-Pakistan.

What is a beginning? What does it mean to begin and why does that matter? How do we determine the starting point for our projects, ambitions, aspirations and dreams, and what does this reveal about us as a people, as human-folk? Edward Said argues that how we structure and define our starting points sets the tone and determines our course of action. Starting points reveal what we deem to be of concern, and what not. They also lay bare the conditions upon which we seek to inquire: marking the point of entry means we set the parameters, standards and boundaries of our process. In Muslim Futures, we could say that the point of departure is one whereby we question what would happen if we imagine the future from a Muslim positionality. The first part of the sentence, “what would happen”, inhabits and signifies a kind of cautious courage, a kind of dare, an invitation to ponder – but of what, and to whom and why? The second part of the question emphasizes the intended actor – a Muslim. What can this particular positionality offer to the discussion on futures, and why should we care about this at all? Here, I seek to reflect upon these questions; not to find a definite answer so much as to invite the reader to stand still, by the important art of asking questions that matter. For Muslim Futures does not start with an answer – it starts with a question. It is inquisitive, it is open-ended, it is curious, it seeks to explore, wonder about and exchange ideas. Scholar John Woolbridge says that asking questions is half of the Islamic experience. It is a dialectic, but it ought not to come without scrutiny – and so standing still by the question means standing still by and within ourselves. Here goes.

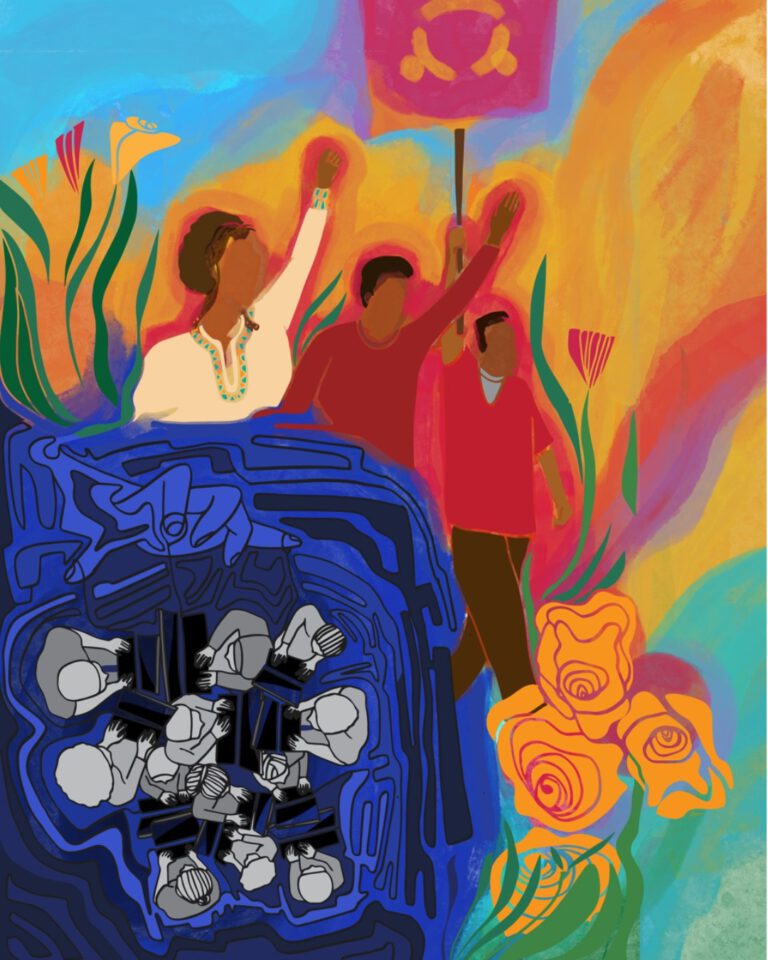

Taking the question of what would happen if we imagine the future from a Muslim positionality, in my view, speaks mainly to two elements: the idea of liberation and the notion of urgency. It is a liberatory question for, generally speaking, the creative energy of Muslims in the West tends to be usurped in having to defend, explain or placate the very notion and idea of their humanity and existence. To defend ourselves and the 1,400 years of history that underline the tradition which ushers us to a spiritual home. To engage in a one-sided epistemological, emotional, political and psychological labor wherein one ought to justify one’s presence, history, future, one’s body, mind, and soul, all at once. It is an existential violence, for what is at stake is usually one’s moral position – one is categorized as either a “good” or a “bad” Muslim depending on how one answers. You have to be outspokenly anti-ISIS, anti-Taliban, wave the “not in my name banner” out, loud and proud. When something happens, you have to ready yourself mentally to be spokesperson and representative – for you are not your own person, you are two billion people at any given moment in time. Not just that. You are any Muslim who has ever walked on this planet, and everything you do is Muslim. You are simple, timeless, rigid, iced – dead. All at the same time as you are expected to keep your distance, pledge your allegiance outspokenly to that which outwardly states it does not accommodate your personhood.

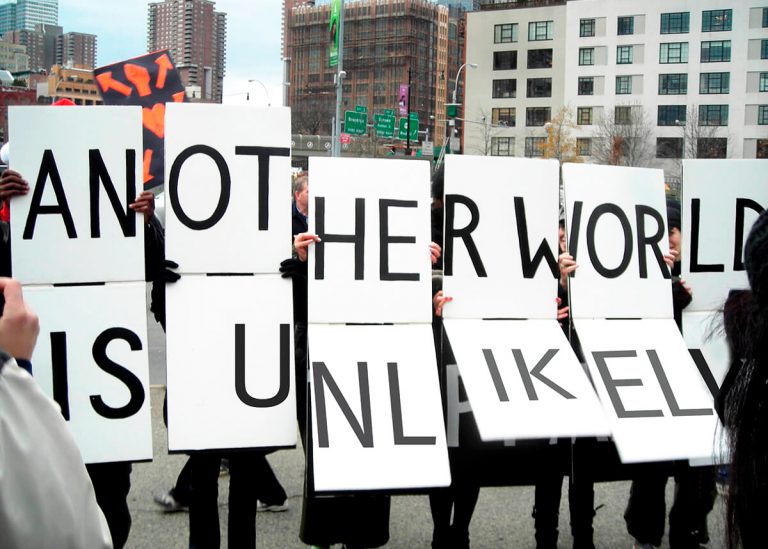

When most of your energy goes to defending and explaining, little goes to creating and building – imagining. By asking the question of what would happen, we actually mean to say: what would happen if we STOP answering your questions, if we stop quenching your thirst and your fears, and instead start addressing our own? What would happen if we recenter the axis? It does not mean that we do not address others who are not Muslim in our imagination, that we do not learn and engage with others, that we become insular and put our hands on our ears, eyes, and hearts – but it does subvert the content, structure, and form of our project. Instead of answering for the horrific acts of the Taliban in Afghanistan, for which we hold no individual responsibility, or instead of cutting off our ties with our ancestries as some purportedly assimilated Muslims wish to do, we put our energy into reimagining another kind of space – a realm, where we look into what we desire, aspire to, and wish to accomplish. It is therefore liberatory – liberating us from the burden that is the often one-sided labor of explicating our human condition, and instead rerouting that energy into something that replenishes our inner vaults. So yes, what would happen when such a space is created? When we can come together and address these issues from a solutions-based perspective with an inspirational energy, instead of one that depletes the soul?

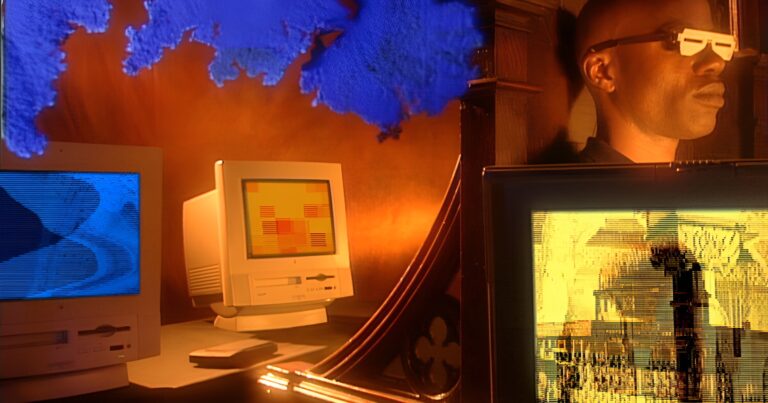

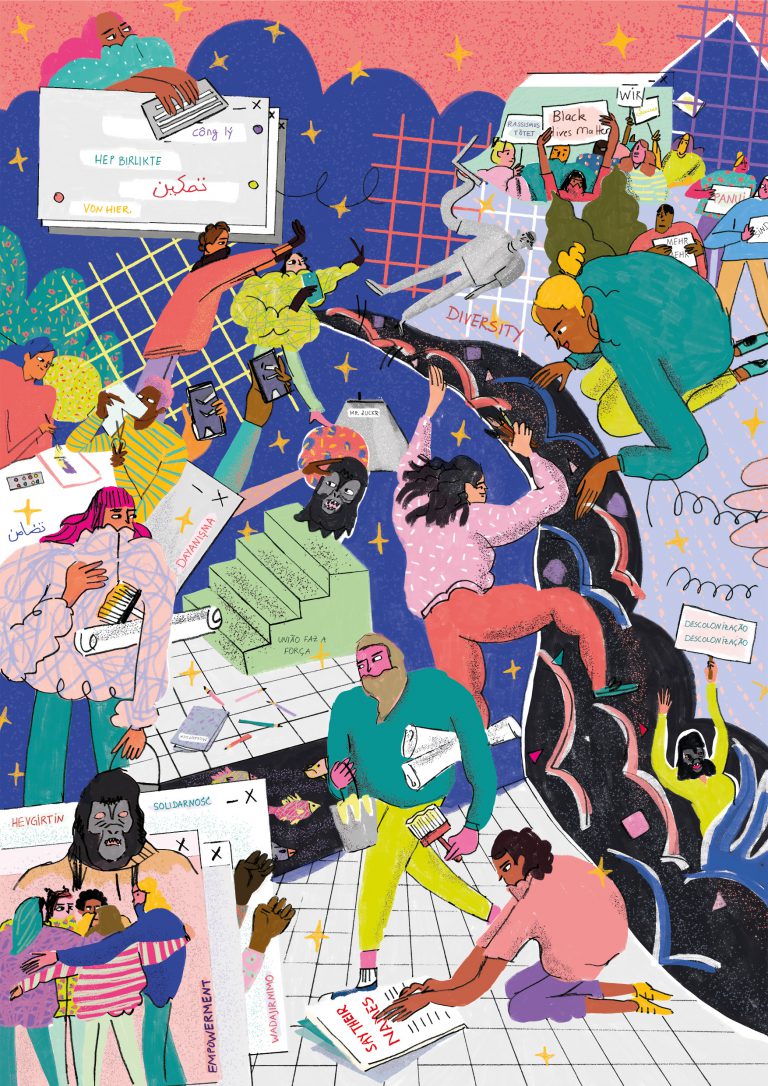

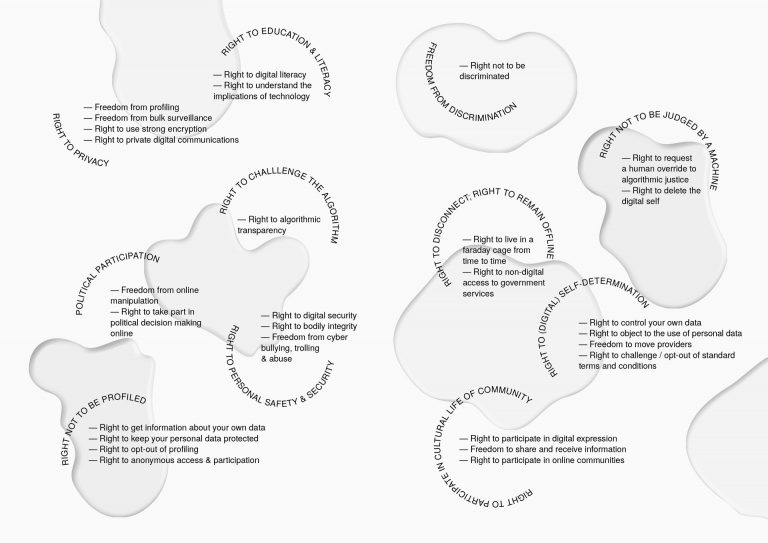

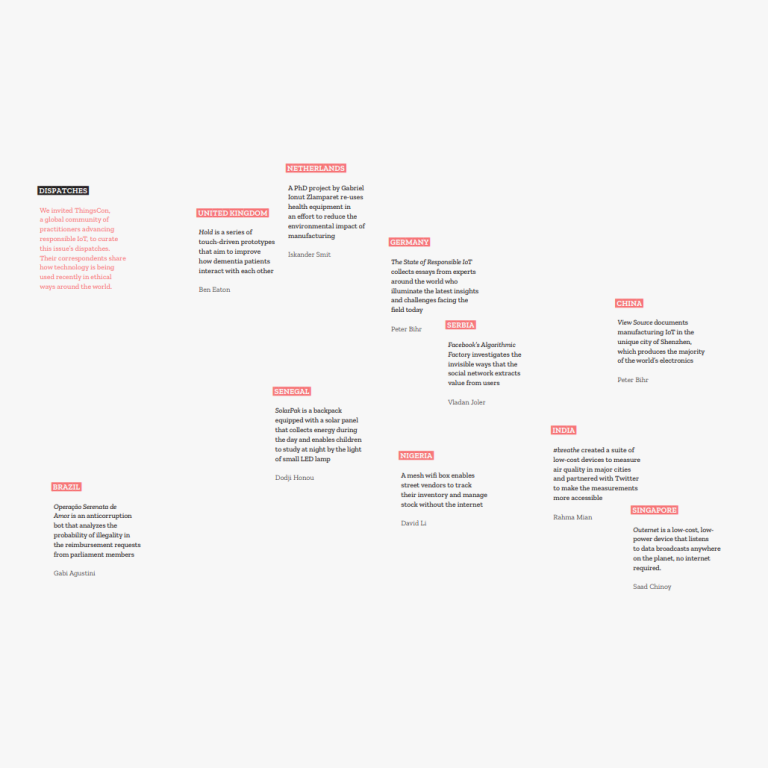

At the heart of this urgent question are the ethical issues that we face as humanity today. Muslim Futures mainly deals with questions pertaining to utopias (or dystopias, as warnings), centering questions that all of us deal with – food scarcity, climate change, digital warfare, consumerism and hyper capitalism, poverty, access to healthcare and education, the unfair distribution of resources. The world is burning literally and figuratively, and at the same time, the ability to reimagine remains in the hands of those who have the privilege to do so. Taking up space, time and effort to reimagine alternative futures ought to be a project in which multiple visions coincide, in which multiple experiences and perspectives find an arena for exchange. This public square of imaginations and ideas tends to be largely secular, and centered on the global North, where one finds the most hoarding of any kind of resources. In a conversation I had with Ouassima Laabich, the curator of this special issue, she mentioned how Saadiya Hartman said that policing the imagination is a significant part of oppression. Most of us have to make do with our daily struggles and focus on surviving, so the world only gets to be reimagined and “futured” through those of us who have the time and space to do so. The act of reimagining from the margins is therefore a radical act in and out of itself.

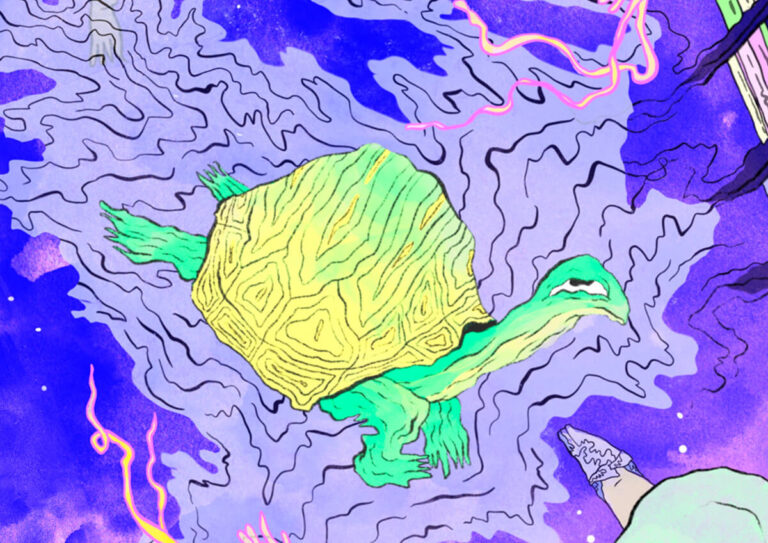

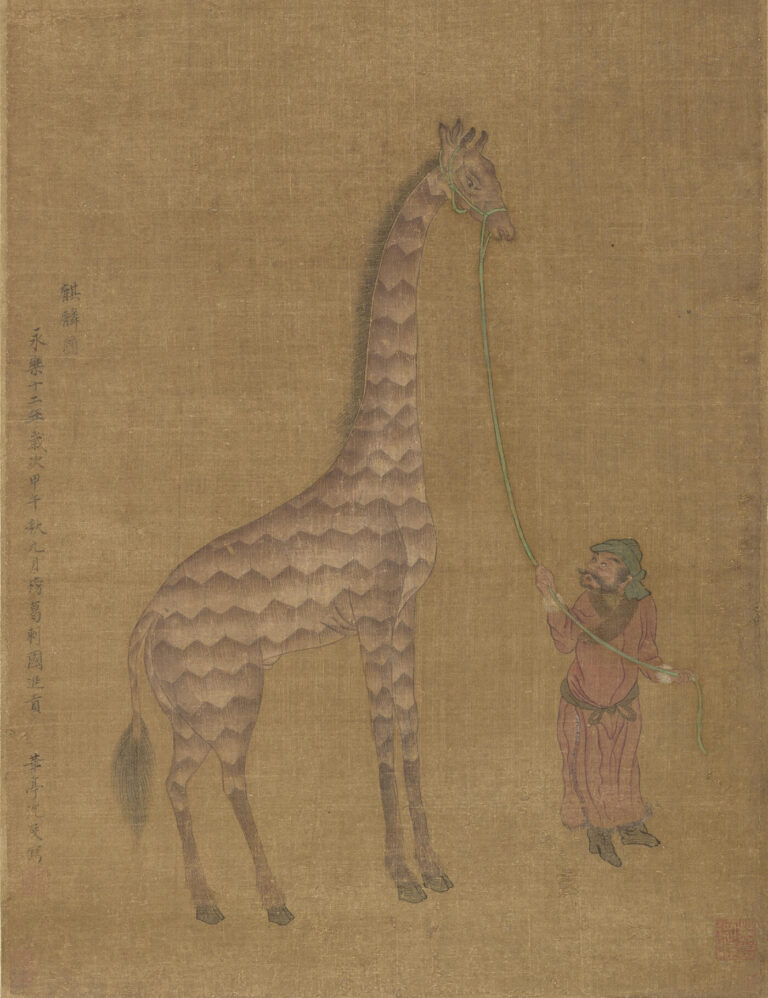

I would like to finish by offering a few notes on Muslim positionality. Muslim Futures aims to be a decolonial exercise. However, despite having the aspiration and ethical commitment to include other ways of making and creating knowledge than those of the Eurocentric kind, decoloniality nevertheless remains largely secular. By contrast, the entry point for Muslims to reimagine their futures is not other humans – it is that which we can not see, yet have submitted belief to. It is God, and all that resides in what we call the Unseen (al Ghayb). Accordingly, our idea of imagination is also explained and experienced differently. Imagination, Islamically, is an in-between world. Between the spiritual and the material world, it is between what we can and cannot see. It is thus not anchored within an individual, as is the case with secular understandings of imagination. Instead, it is something that we step into, between presence and absence, a place we cannot pinpoint easily. We access it when we dream, for example, and dream interpretation is therefore considered to be an important medium which influences real decision-making processes. In the Muslim Futures Berlin exhibition, several references were made to dream interpretation. An exhibition plaque explained how, through imagination, one can be attuned to both the material and immaterial at the same time: “I draw from the connections, between here and there, me and you, and the (in)visible”. Additionally, it is believed that what we imagine draws from our surroundings, instead of actually creating something from scratch, which we are not able to do, for only God is the true creator (al Khaliq, the Creator). A winged dragon, for instance, is inspired by lizards and the wings of a bird. World building in fantasies is inspired by what we have encountered, in some form, in real life. When we imagine, we are also spiritual, for we are in conversation with God’s creations. As Ebrahim Moosa notes, we thus share our imagination with our ancestors and with our descendants; it is therefore important to engage the imagination in order to interact creatively with a wide array of intellectual and cultural traditions. One of the most important thinkers in Islam, Al Ghazali, says that humanity’s survival depends upon its ability to be creative, for it is within the imagination that we can catch glimpses of opportunities and limitations.

The Islamic perspective on the importance of imagination and dreams as vessels through which we can tap into other worlds and reveal potentialities or warnings coincides with the fact that the future is also located in the Unseen. Taking one’s Muslim positionality seriously in this endeavor also means carving out spaces for the kinds of interpretation whereby one takes God’s existence, and thus the existence of the Unseen, as a starting point; it humbles one’s standing in the world. Islamically, humans are seen as the stewards of the planet, safeguarding and protecting all of God’s creations; the pursuit of knowledge and activity of imagining are intended not as a means of controlling or subjecting people, exploiting or dominating them, but to improve one’s ability to care. When we take God as the starting point, there is no room for the deification of self. One lives in the world, not above it.

Imagining alternative futures from a Muslim positionality thus asks us not only to subvert contemporary dynamics wherein Muslims must defend and exhaust themselves in explaining women’s rights, yet again; it also asks us to take a moment and, indeed, consider what it would mean to offer something useful from an Islamically-inspired vantage point. What it would mean to take up space in this marketplace of ideas on how to live (in the words of one of the most important thinkers of Islamic thought, Abderrahman Taha) an ethical life – especially in this modern world where most of our pleasures are dependent upon the suffering of others. When so much energy is subsumed by apologetics, and by defending, one is distracted from looking inwardly, from spiritually anchoring oneself and asking the questions that actually matter – why is the plight of humanity as it is, and what can we offer? As French thinker Charles Baudelaire wrote, “the only long work is the work one dare not begin”. We began 1,400 years ago, and it is time to begin again, now, in the present, for that is where the future can be found.