10.04.2025

Is there a threshold for grief? A limit beyond which the unthinkable becomes all you can think about, after which grief swallows you whole? I find myself thinking about this more and more, while I struggle under the weight of grief-from-afar, watching children killed in Palestine day after day, at a rate that my heart can’t comprehend. I feel like a balloon filled with water: all that holds it in is a thin and tensely stretched surface. One little pinprick and it’ll all come gushing out.

I remain convinced that if cis men were the ones to carry life, to become pregnant and to give birth, lives would be more valued, wars less casually begun. A life is not just a life; it’s a whole universe of hopes and dreams.

When I was pregnant, a friend told me her father described having children as “having one of your vital organs walking around in the world without you”. The pain of knowing you can’t always keep them safe, while knowing you can’t survive without them.

I begin relishing stretched-out bedtimes with my children, secretly rejoicing when one of them wants to cuddle with Mama before bed. Lying down next to them, feeling their warm breath on my skin, putting my hand over their hearts to feel their heartbeat makes me feel better able to protect them. I repeat this, over and over, feeling alternately guilty and grateful, guilty and grateful. Grateful that the luck of the draw means I can hold my babies close and keep them safe; guilty that other mothers see their babies starve and be killed. These mothers who are unable to bury their children, who must watch them suffer, over and over and over while the world does absolutely nothing.

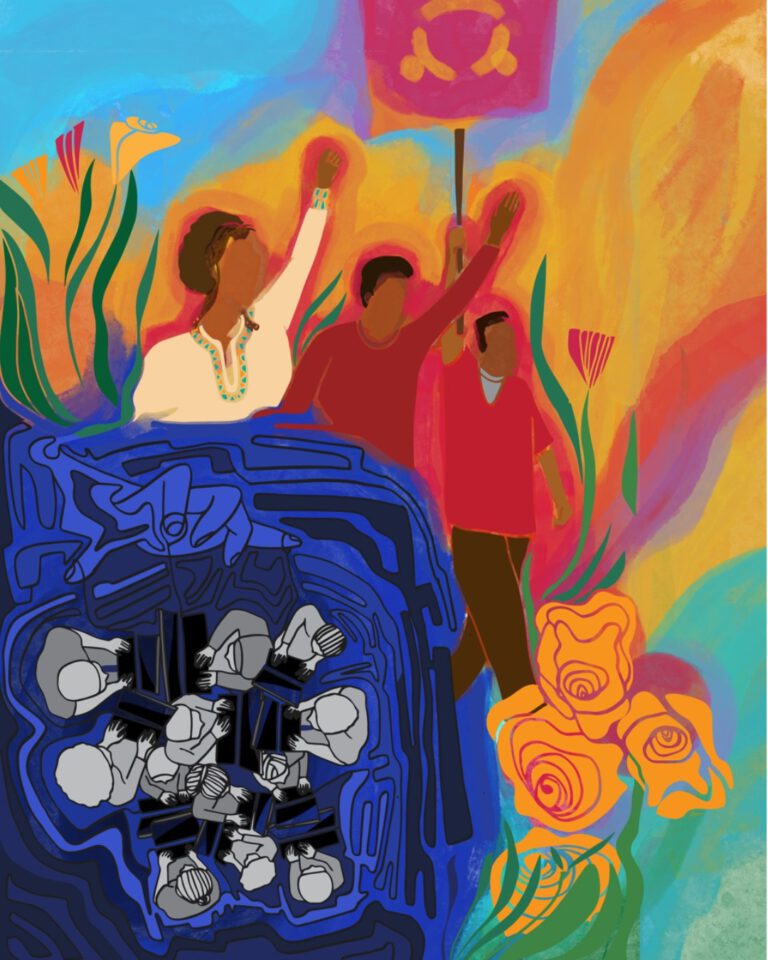

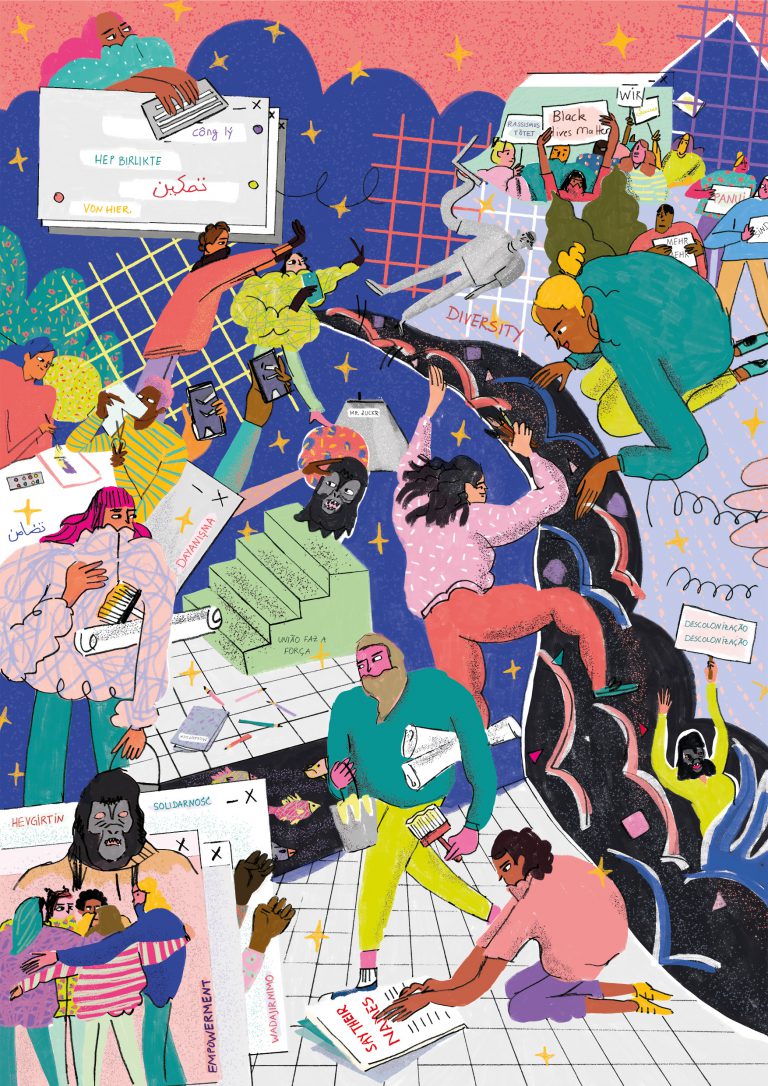

“We honour the dead, and we fight like hell for the living” we chant, at a memorial for murdered Women Human Rights Defenders, at the AWID Forum in 2016, a gathering of feminist activists from around the world, that year held in Brazil. I’m in awe at how grief and anger for these women’s deaths is held by the collective and galvanised into something tangible – something that gives us power and strength instead of taking it away.

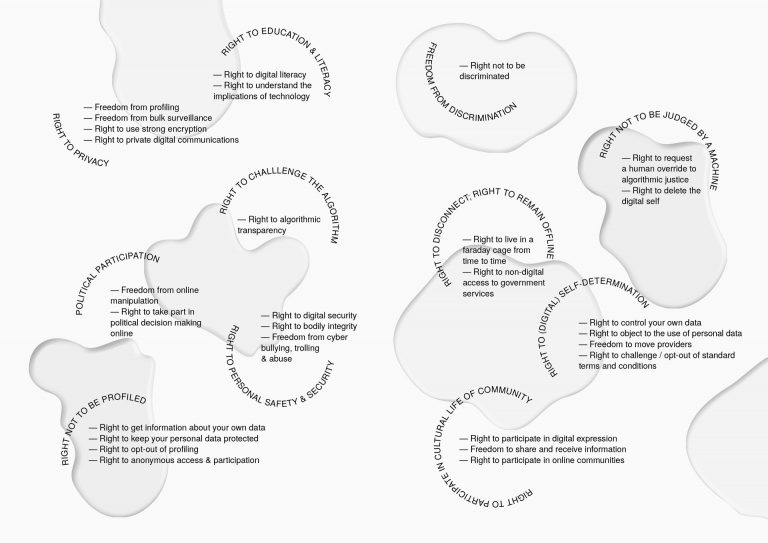

This, I later learn, is collective resonance – a way in which grief, collectively held, can be processed with others. It speaks to the difference between grief and trauma: grief brings us together, just as trauma splits us apart. Tobi Ayé, a grief worker and somatic practitioner from Benin, tells us that grief is loss; not only loss of human life, though it is the most recognised form of grief, in the western world at least, but just the loss of anything.

Hearing this makes me think of things I’ve grieved in the past that I didn’t allow myself to hold as actual grief – imagined realities that never came to be, potential futures that won’t happen, pivotal political moments that went differently to how I’d hoped.

I realise, in my water balloon state, that I need a place to let out all these emotions. I see a social media post for a collective grieving session in response to what’s happening in Palestine, which I sign up to immediately.

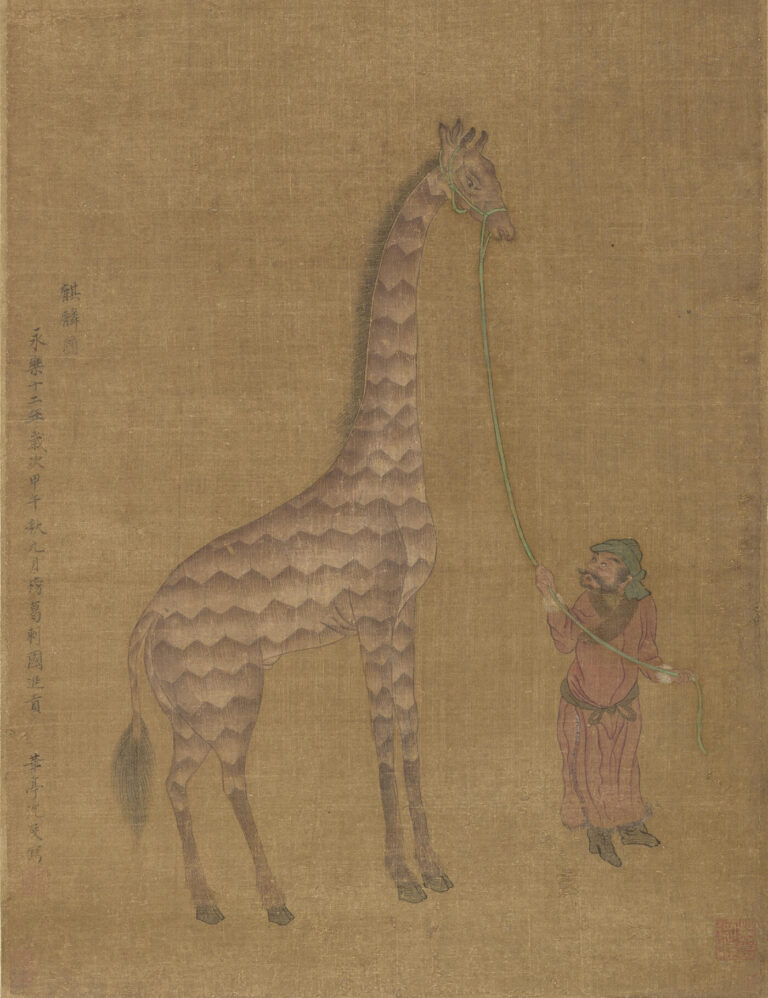

The session is attended by the Grieving Doves, a collective of women in Berlin, grieving the souls killed by bombs. The doves wear wings, made up of pieces of material upon which are written the names and ages of people killed in Palestine.

The first name I read is Musab Al-Rahman, aged 3. This child, who shares my surname, died when he was younger than my own child, who has barely started his life. I can’t fathom it; the pain that his family must feel, the cruelty with which these thousands of lives have been taken away.

But beyond the cruelty of the ones doing the killing is the cruelty of those who condone it, those who look away, those who allow it to happen or make excuses for it, who decide not to speak up against it. Germany, where I live, feels like it is full of these people: journalists who choose not to write about the repression of Palestinians and pro-Palestine activists, civil society which looks away when freedom of expression becomes a thing of the past for some.

That Germany, of all places, would be the place to allow the targeted persecution of a minority group, that German society would collectively look away, to declare it “too complex” to address. That at this moment, at which one would hope education would have played a role in encouraging Germans to think critically about power, to think about oppression and the oppressed, to see how violence is being used, upon whom and by whom, is the moment where German society shows its true colours, looking away once again. The irony is not lost.

I find myself talking about Palestine a lot, wanting to understand what is going on, why people aren’t speaking up, why they seem unable to understand what’s going on. It fills me with rage when people ask why I care so much, whether I have family there myself, if I have friends in Gaza. As if that’s the only reason to care?

No, I reply. I’m a human being, they’re human beings. Isn’t that enough?

Apparently not. I’m faced, for the first time in 13 years, with almost weekly racism, Islamophobia, xenophobia, sometimes all three, sometimes even acknowledged and recognised, most of the time by well-meaning white liberal Germans who are convinced they’re anything but racist.

A German woman tells me she feels sad but doesn’t quite understand where my anger is coming from. Hearing that makes me feel like steam must be coming out of my ears, my blood boiling. It’s the exact opposite I don’t understand. How is it that people see what is going on and feel anything but rage? It’s not a rhetorical question; I truly want to know. I feel sometimes like I’m losing my mind, walking around full of rage and grief while German people around me seem able to tune out the violence, even while living in a neighbourhood with a huge Palestinian diaspora. I struggle to even imagine the pain they must be feeling; this intensifying violence and genocide, combined with the decades of ongoing violence on so many levels, exacerbated by the denial of that violence in the face of irrefutable evidence.

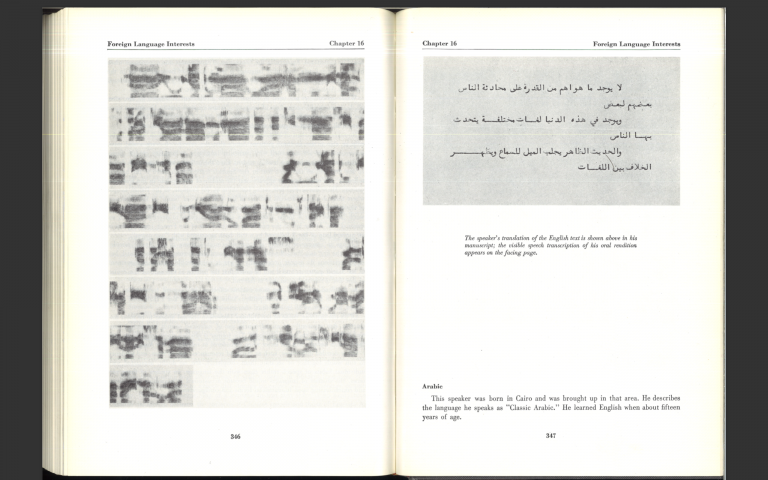

This denial of violence is something my family know well. The 1971 genocide in Bangladesh remains, to this day, unacknowledged by the UN, the US, and the perpetrators, Pakistan. Bangladesh’s support for Palestine also goes back a long way. Bangladesh has never officially established diplomatic ties with Israel, and refuses to recognise the state of Israel.

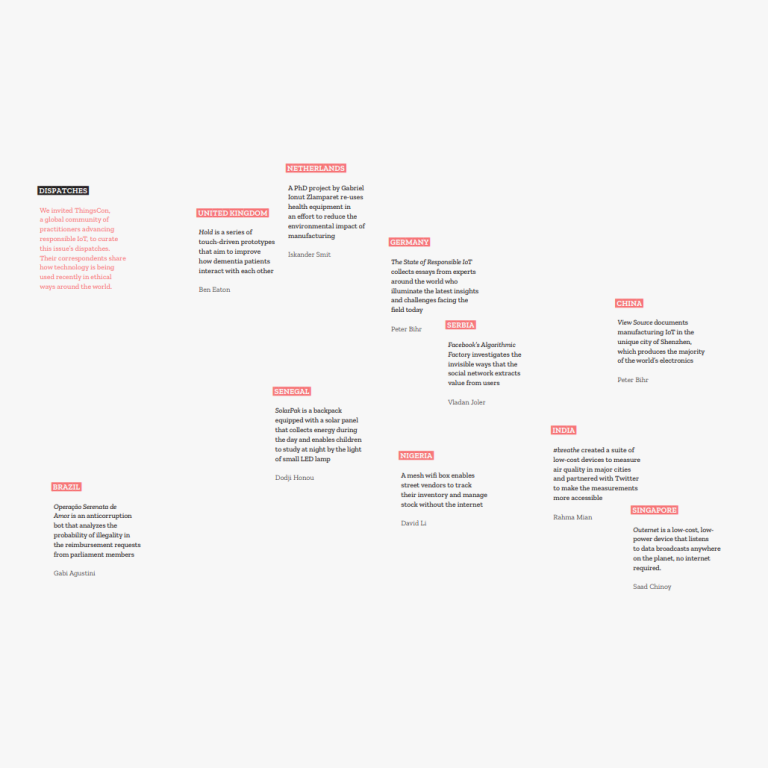

It feels, right now, like there is so much to grieve it’s overwhelming. At the closing plenary of the 2024 AWID Forum in Bangkok, speakers from Tigray, Patagonia, Iran, Georgia, Sudan, Haiti and more shared their struggles and pain, and their calls for solidarity. Their pain was almost overwhelming, their courage inspiring.

The AWID Forum gathered over 4,000 feminists from all over the world to dream, plan, meet and feel together. It felt to me like there were so many people in that water balloon state. There were spaces to feel together, but also a palpable sense that the struggles, for almost everyone, were urgent, important, more-crucial-than-ever.

But there were also spaces for coming together and dreaming, and for remembering those before us who dreamt, and who made their dreams a reality so that we could be here.

I think of my Nanu, whose life was so different to mine it seems unimaginable that we’re only two generations apart. I suspect I might be living her wildest dreams, and I wonder what it would look like for my potential future grandchildren to live my wildest dreams. I struggle, in this state, to even picture what that might be, but it motivates me to create a space where I can begin to put that picture together.

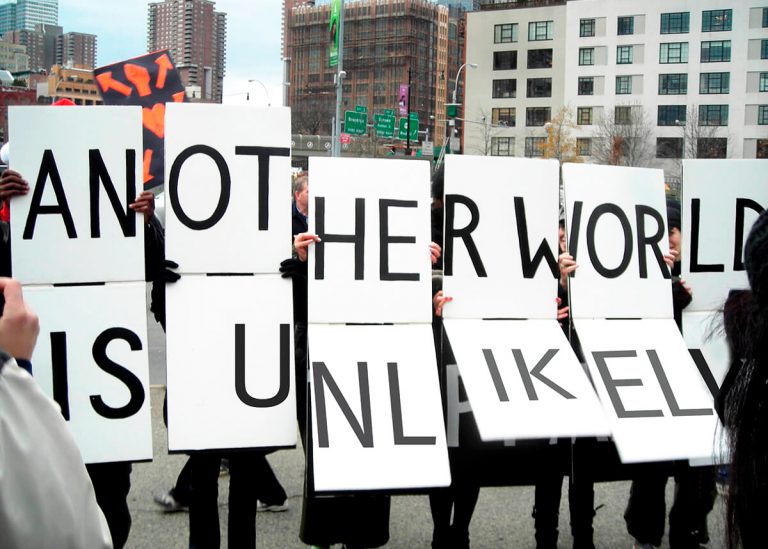

Those liberated futures – we must dream them before they can happen. Maybe I’m being dramatic, but it feels like right now there is so much teetering on the brink, a world burning to be reborn. Out of these ashes, out of this pain and grief, we absolutely must make this new world something to be proud of.